by Lance Hill | May 27, 2022 | How To, Mirliton

Spring mirlitons are normally sold unsprouted because they are picked fresh from the vine in early May. The first step before planting is to sprout the mirliton. You can speed the process by incubating it—keeping it as warm as possible. If it is above 80° outside, place the mirliton in a shaded area. Or you can incubate it inside your home by placing it in a small plastic trash can or 5-gallon container with a lamp or small heating pad on low. The ideal temperature is 80°-85°. This will promote rapid sprouting within 10-14 days. (here is how I did it)

As soon as the seed begins to emerge (sticks out its tongue), it needs to be planted—but differently from the fall ones. In May, temperatures can run in the 90s along the Gulf Coast, and I have found that sometimes they won’t send up a shoot in extreme heat. Instead, the shoot spirals under the seed. (Figure 1).

The solution is simple. Plant the sprout as you normally would, but put a temporary shade cover over it —a milk crate with a piece of shade cloth over it or a piece of cardboard on top will work fine. Cover the crate with chicken wire to ward off varmints. Once the shoot emerges, remove the crate and stake up the vine.

Figure 1.

by David Hubbell | Apr 7, 2022 | Mirliton

Mirliton.org Certified Pedigrees

We have noticed an uptick in interest from folks on social media looking to acquire seed mirliton or mirliton plants. As we have always preached, to be successful at growing mirlitons in Louisiana and the neighboring states, one must start with heirloom varieties suited for the Gulf Coast. As a result of our efforts in saving the Ishreal Thibodeaux white mirliton variety, there appears to be a lot of people posting they have received some of that variety to grow; however, it has also been noted another white variety has recently turned up as well as some imports from Latin America.

In an effort to help ensure future growers are actually growing the varieties they think they are’ we will start issuing Pedigree Certification Acknowledgment certificates to those varieties that have been already identified (e.g., Ishreal Thibodeaux, Papa Sylvest, Remondet-Perque, etc.) or will be identified by Mirliton.org. These will be free PDFs emailed to recipients so they can be kept on record with unique certification numbers so we can establish future pedigree claims. They can provide a printed copy to individuals who buy from them as proof of variety claim.

Image 1: Sample Certificate Header

The first round will focus on the Ishreal Thibodeaux growers. This may be a time-consuming process depending on the records available and may not always yield a certificate if we cannot establish the original source or verify based off of physical description and pictures. If you have a viable established mirliton vine of 3+ years and would like to be considered for a certificate, please contact David Hubbell at rpcajun2r@gmail.com .

by David Hubbell | Mar 26, 2022 | Mirliton

As many of you know, we have added the Mirliton Pronunciation button to the top of the page that gives you a link to how many well-known native Louisianians pronounce the word Mirliton. The link will take you to the first pronunciation of Lolis Eric Elie, then should proceed down the playlist. If it doesn’t simply click here for the whole playlist: How Do You Say MILRITON?

So far, we have:

Season 1:

Lolis Eric Elie

Glen Pitre

Don Dubuc

Julie and Vance Vaucresson

Chef Frank Brigtsen

Liz Williams

Renee Lapeyrolerie

Chef Jeremy Langlois

Spuddy Faucheaux

Marcelle Bienvenu

Jay Schexnaydre

Jerry Folse

“Uncle” Larry Roussel

Ken Wells

Bryanne Bellman

Mark Bologna

Captain Luka Cutura

Miss Louisiana 2021 – Julie Claire Williams

Nancy Tregre Wilson

Chef Amy Sins

Marissa Rabalais Turner

Jimmy Babin

Lester Folse

Poppy Tooker

The Children of Ishreal Thibodeaux

Chef Tommy Centola

Season 2:

Kernis Louviere

Maureen Brennan and Spud McConnell

Jyl Benson

Peggy Scott Laborde

We have reached out to many more folks and hope to add to our list for Season 2. If you know of a Louisiana native that you would like to hear, say the word MIRLITON, simply send me an email at rpcajun2r@gmail.com and I will see what I can do.

Thank you also to Poppy Tooker for showcasing the project on her recent episode of Louisiana Eats!

Thank you for watching!

by David Hubbell | Jan 28, 2022 | Mirliton

Background:

Since June 20th, 2020, Mirliton.org has been working with growers throughout the country on the Ishreal Thibodeaux White Mirliton Preservation Project in an attempt to bring back, from the brink of extinction, this rare ivory white variety of the mirliton grown and cared for over four decades by Opelousas, Louisiana’s Ishreal Thibodeaux. If you haven’t already checked out the last Update on the Ishreal Thibodeaux White Mirliton Preservation Project – 2nd Quarter 2021 then please do so to see the progress up to that point. It links back to the other updates which contain an in depth look at all of our growers and efforts from the start of the project.

Grower Update:

As mentioned in the previous updates, we were able to expand our growing efforts to 9 new growers; mostly in Louisiana but some in Texas. This is in addition to our existing six from last year. Sadly, it looks like our Carolina and Alabama plants did not survive into the 2021 growing season. Our sincere hope is to resupply these folks with plants in early March 2022 for a second try.

Reports from the Field:

The last half of 2021 presented many challenges to the growers. In particular, a major part of those in Louisiana were right in the path of destruction of Hurricane Ida. Many lost their vines and the great progress they were making, but that loss seems inconsequential compared to the loss of life and property many in that area felt. Fortunately, our growers who faced setbacks are raring to try again in 2022 and we are making efforts to get them reestablished. Attached are a series of updates and photos from our new and existing growers from the last half of the year.

Wade Guidry – Cutoff, LA

Wade reports that. “(We) lost all our garden including Ishreal Thibodaux’s. But hoping we can get new ones to start from scratch again!” – September 23, 2021. Good news for us all is that we have helped locate more IT mirlitons for Wade to start over in 2022.

David Duvic – West Felicians Parish, LA

“Plants are doing well. Starting to flower. Spraying with copper every 7-10 days hoping to control mildew/anthracnose. So far, I am winning. If anyone knows of a particular product that works well, please let me know.” – September 23, 2021. As you can see, David efforts yielded a very nice crop.

Image 1. David Duvic’s IT mirliton in November 2021

Christopher Brooks – Opelousas, LA

“Bad news to report on my end. Something (I suspect a rabbit) ate both my vines off at the ground. I was hoping that they would re-sprout and resume growing. Unfortunately, they have not. One did put up a start but died back down.” – September 22, 2021. As with Wade, we have helped Christopher locate some more to start over in 2022.

Laken Thomas -Lake Charles, LA

“Unfortunately, my plants didn’t make it. We have been having terrible weather events in SWLA. After I moved them outside their health declined and never recovered. I put up wind barriers and built an area specific for their growing needs but it just wasn’t enough ☹“Fortunately, Laken located some more IT mirlitons from another source so they are set for 2022!

Brad Langlanais – Lafayette, LA

“Unfortunately, I lost my plant back in July from over fertilizing it. It was looking so good too!” – December 2022. Brad was able to locate some of the new white mirlitons a grower out of Mississippi made available in December. We don’t believe these are the Ishreal Thibodeaux variety, but we will find out after growing them the differences between the two.

So far, our Texas growers aren’t doing too bad at all. Please check out their phenomenal progress!

Kevin de Santiago – Round Rock, TX

Kevin has the distinction of being the first gardener in Texas to successfully grow the Ishreal Thibodeaux variety. Here are 4 beautiful specimens.

He notes – “There are eleven more that have reached the “this is happening” size. The vine keeps putting out flowers and our warm temps are holding up.” – December 4, 2021.

Image 2. Kevin de Santiago’s IT mirlitons December 10, 2021

Sadly, shortly after he reported, “The freeze was a lot harder than anticipated.”

Image 3. Kevin de Santiago’s IT mirlitons in early December 13, 2021

Image 4. Sasi Vajha of Houston photographed this IT mirliton down on Galveston Island provided to her by Kevin De Santiago December 23, 2021. We at Mirliton.org really love this shot!

Alan Raymond – Kingwood, TX

Alan reported that “I have 6 mirliton fruit developing. A few photos are attached. The largest is about 4 inches long.”

I

I

mage 5. Alan Raymond’s IT mirlitons in early December 2021

Image 6. Alan Raymond’s IT mirlitons in early December 2021

Image 7. Alan Raymond’s IT mirlitons in early December 2021

From our established growers:

Paul D’anna, Master Mirliton Grower – Metairie, LA

Paul’s holiday update –

Image 8. The Mirliton Man of Metairie, Mr. Paul D’Anna inspecting some IT mirlitons in December. Paul is in his element! Thank you, Renee Lapeyrolerie, for this great picture!

James Cobb– Houma, LA

James reports

“2 nice ones growing. Have about 1/2 dozen more about golf ball size and loads of tiny ones & flowers. Been some rough going the last year but hanging in there. There’s hope.” – November 2021

Image 9. James Cobb IT mirlitons in early November 2021

Chef John Folse – Baton Rouge, LA

“All good here. Vines very full and still picking and begin to plant for greenhouse. Many are already spreading roots. Big year again.” – December 2021

Once again Chef John and his great staff at White Oak Estates and Gardens have put aside some for the Ishreal Thibodeaux White Mirliton Preservation Project so that folks like Wade, Christopher, and Carolina grower Keith Mearns can give it another shot!

Image 10. White Oak Estates and Gardens IT mirlitons being potted in the greenhouse in early January 2022

I believe these are all of the photos I have from our growers. I imagine you are as impressed with their progress as I am. This is an amazing finish for 2021 compared to where we were in December 2020! Kudos to all the growers and continued success as we head into winter and work on overwintering and preparing for the 2022 growing season.

Additional Louisiana Growers – Independent of the formal group

Jay Thibodeaux – Opelousas, LA

Jay bought some from Paul D’Anna last year and had a great year making over 100 available for sale. Look at the size of this one!

Image 11. Jay Thibodeaux’s whopper IT mirliton December 2021

Image 12. Jay Thibodeaux’s display of some beautiful IT mirliton December 2021

Buddy and Charlotte Baham – Algiers, LA–

Back in March 2021, we learned of another Ishreal Thibodeaux grower that had gotten some of the original mirlitons Dr. Lance Hill shared with growers back in 2013. We were very pleasantly surprised that they had been growing these in abundance in Algiers for over 8 years. They generously made some available for sale back in March and shared some pictures of their Fall 2021 bounty. Check out these awesome pictures by Buddy Baham.

Image 13. Look at the size of those IT Mirlitons from Buddy and Charlotte Bahams!

Image 14. Buddy and Charlotte’s mirliton structure in Algiers!

Image 15. A cluster of the IT Mirlitons in Algiers

Image 16. The IT vine has found a wonderful place to thrive in Algiers!

Tee Shirt Campaign:

We continue to have steady sales of our Ishreal Thibodeaux White Mirliton Preservation Project tee shirts. The purchase of these shirts helps us continue our efforts to preserve and promote the work of Mirliton.org. If you are interested in purchasing one, these shirts are available as a special offering for those wishing to donate $30 per shirt to Mirliton.org. To order your own, simply click here or send me an email at rpcajun2r@gmail.com.

Image 17. The official project Tee Shirt

Image 18. The official tee shirt of The Ishreal Thibodeaux White Mirliton Preservation Project

Education and Inspiration Through Food:

One of the many other projects we conducted in 2021 was a fun little effort engaging the help of many notable south Louisianians to provide instructional videos on how they say the word, mirliton. The Mirliton Pronunciation Project was a great success and we have 27 episodes from the first pass and will be working on many more for the second round. If you haven’t seen them, please check them out by clicking on the following playlist: Mirliton Pronunciation Project. You’ll see many familiar Louisiana names like Chef Frank Brigtsen, writer Lolis Eric Elie, director Glen Pitre, outdoorsman Don Dubuc and many many more. I also hope you check out episode 26 below with our very special guests – the children of Mr. Ishreal Thibodeaux! Let us know what you think! Click below or here!

Image 19. The children of Ishreal Thibodeaux help out with the Mirliton Pronunciation Project

Chef John Folse provides another great recipe using the IT Mirliton found via WAFB’s website. Check out this Mirliton Custard recipe here: Mirliton Custard (wafb.com)

In addition to the great information regarding the growing of mirliton, don’t forget we have a section completely devoted to recipes found below: International Mirliton/Chayote Recipes – Mirliton Dr. Hill has continued to add great recipes as he comes across them. Check it out and start planning your 2022 mirliton menus now!

Finally, I had a chance to help spread the word on our mirliton efforts via three platforms. I gave a general hourlong mirliton talk via Zoom to the Pensacola Organic Gardening Club in October, followed by the very enjoyable and educational Tip of The Tongue podcast (part of the Nitty Grit Network) which falls under the umbrella of the great Southern Food and Beverage Museum in New Orleans. Thank you again to the founder and show host, Liz Williams for having me as her guest. You can check out the interview here: Tip of the Tongue 103: Mirliton, Chayote and Christophene — Southern Food & Beverage Foundation

I then finished off the year sharing our efforts on one of New Orleans’ great radio institutions, Tom & Mary Ann Fitzmorris’ The Food Show. You can find my 30-minute segment about an hour in here: THE FOOD SHOW – DECEMBER 10, 2021 – WGSO 990AM

Final Thoughts for the 2021 Growing Season:

This final update of the 2021 growing season should clearly give the reader an idea that the program is doing quite well despite our issues due to Ida. I am really impressed and inspired by what I am seeing from our Texas growers and the independent work done by Buddy & Charlotte Baham and Jay Thibodeaux are enhancing and supporting our work. The goal for the Ishreal Thibodeaux White Mirliton Project all along has been to preserve and then develop a network of growers that are able to provide others interested in this variety a reliable source to call upon as the we make a resurgence. It really looks like the we are a lot closer to that point then I expected we’d be after two years. At last count, we have 7 growers with great productive vines and perhaps 50+ independent growers going into 2022! I really believe by the end of 2022 we will have a great network of Ishreal Thibodeaux growers throughout the Gulf South that should be able to make this variety available to all who are interested in growing them.

As a final note, I have added only a few names to the third wave of growers in 2022 but if still interested in the project, please check out this link. Thank you all for the interest and support in 2021 and we wish you, your family, and friends a safe, healthy, and wonderful spring growing season.

If you have any comments, questions, or suggestions, please send them to me David J. Hubbell at rpcajun2r@gmail.com. Thank you.

by David Hubbell | Sep 24, 2021 | Mirliton

Pioneers in Louisiana Mirliton History

John Burns Sr. (1884-1947)

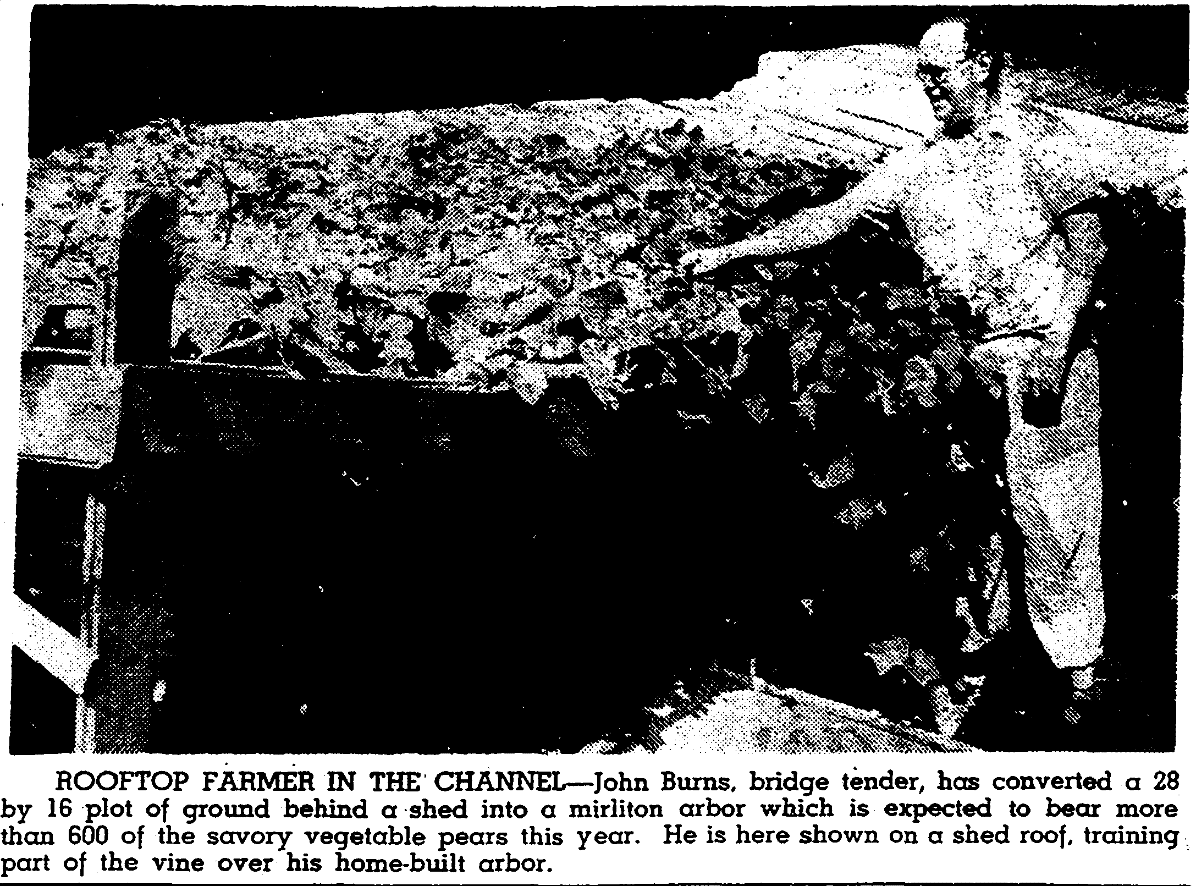

On Thursday September 18, 1941 Hermann B. Deutsch, a reporter for many New Orleans newspapers over his 50+ year career, penned the following on page 8 of the New Orleans Item:

“Each artist chooses his own medium for the attainment of beauty. Wagner worked with music, Rembrandt with oil pigments. Keats with words, Phidias with the sculptor’s chisel. Pavlova with the dance. Cellini with the goldsmith’s mallet, Genthe with camera. But John Burns of New Orleans chose a Mexican vegetable with a French name and American devotees to create beauty in the Irish Channel.”

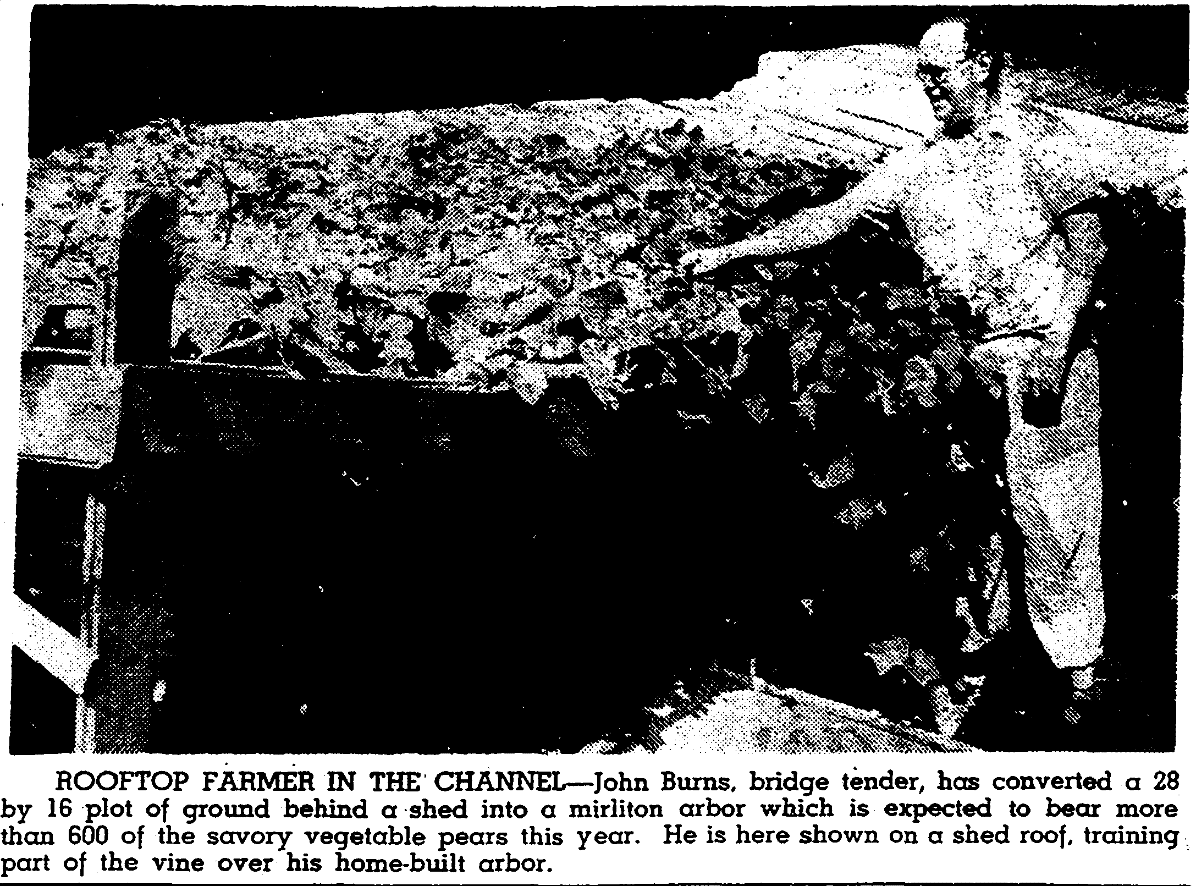

The title of the article was Orleanian Creates Beauty in A Mirliton Arbor1 and ran with the following picture:

Image 1: The New Orleans Item1 Article

When I first read through this article, I was curious as to who was John Burns, what kind of mirliton was he growing, how tall was the arbor given that Mr. Burns was standing on his shed roof, and where exactly was it located in the city?

John Burns Sr.

John Thomas Burns Sr. was born on March 27, 1884 in New Orleans to John Peyton Burns and Catherine Connert and grew up in the city’s 1st Ward. His father was originally from Canada and his mother appears to have been a native New Orleanian. Per the 1900 and 1910 Census2,3, it was recorded that everyone from his parents down to siblings could read, write, and spoke English and that the younger members were enrolled at school. Thus, we can conclude that the family was fairly literate and educated. In his early years in 1910, John held the job of being a Clerk for the railroad. On December 17th, 1913, John married Ellen “Nellie” Lacey. Like John, Ellen was born in New Orleans (March 15, 1884). Ellen’s father was Thomas J. Lacey originally from Ireland and her mother was Mary Smith from New Orleans. The 1930’s census4 lists Ellen as a homemaker who could also read and write. By 1918, when John filled out his WWI Draft Card, he had been working as a longshoreman and the couple had moved to 2419 St. Thomas Street in the neighborhood known as the Irish Channel. John was described as being of medium height at 5’ 5” and medium build with grey eyes and brown hair5. By 1920 John was employed as a “screwman” on the river front6. According to the article “THE 1907 NEW ORLEANS DOCKWORKERS GENERAL STRIKE”7 by Malcom Suber, “The New Orleans screwmen were responsible for tightly packing cotton bales in the holds of the ships. This critical task put them atop the labor force on the docks thus providing the screwmen with the highest wages on the docks.” A similar reference cited on Wikipedia also commented that “their work was highly skilled, required immense strength, and was indispensable to the smooth operation of the waterfront.”8 Thus, we can assume that despite his medium stature, John must have been a pretty strong man in his youth and earned a fairly decent wage. However, from then until 1928, John’s profession was listed in the New Orleans City Directories9 as simply a laborer. In 1928, his occupation is changed to that of Bridge Tender.10 The Bridge Tender is basically one in charge of the bridge ensuring its operation and safety both on the bridge and for the passage in the canal. At the time of the mirliton article, he was the Bridge Tender for the bridge at Broad Street and the New Basin Canal. Today that is basically where Broad crosses the Pontchartrain Expressway near the WLAE studios. Image 211 is a photograph of the south Broad Street side of the bridge in the last few years that John worked there. Around 1946, the city started to fill in the New Basin Canal which was eventually replaced by the Pontchatrain Expressway.

Image 2: South Broad Street bridge over the New Basin Canal (1941-07-09)11

John and Nellie had six children: Eleanor, Lorraine, James Joseph, Rita, John, and Raymond. July 17th, 1925 was a sad day at the Burns residence when one year old John Benedict Burns passed away. The funeral was conducted from the residence the next day and the child was buried in St. Patrick Cemetery #1.12

John Burns appeared in the New Orleans papers a couple of times from 1913 through the 1941 article. In some of the articles he was either the main subject or in a “supporting role”. In September of 1925 he was charged with impersonating an officer after trying to extort $1 (equivalent to about $15.50 today) from a bar owner by showing him a “special badge”13. In this case it appeared that he had been as Bob Cratchit would say “making rather merry” before the event. In 1931, he was credited with saving the lives of those trapped in a cab on the bridge14. However, in 1932, John unfortunately made a poor choice that end up with him in the hospital due to the negligence of an intoxicated driver he rode with15. About 2 years later, he had to be called upon to help police drag the New Basin Canal when a train porter had jumped to his death from the bridge16. After this, there weren’t any more mentions of Mr. Burns excluding the mirliton article and his obituary which appeared in the Tuesday April 15, 1947 edition of the New Orleans Item17.

What Kind of Mirliton?

This question is probably the hardest to answer. The reason being is that mirliton comes in so many sizes, shapes, and colors and until Dr. Lance Hill and Mirliton.org started giving them “names” it was probably described by just that – size, shape, and color. There unfortunately isn’t a picture of Mr. Burn’s mirliton, but they are described “great green bells”. Some things we can glean from the description is that these were rather large mirlitons with a narrow top but a wider flat bottom. Even though the author called them “vegetable pears” he doesn’t describe them as pear shaped. In a lot of cases the mirlitons have a rounded bottom like a pear or avocado. He also only described them as green versus light green and there is no mention of spikiness. Based upon his description, I would venture to guess they might have looked like the Sister Morgan or Joseph Boudreaux varieties.18

Image 3: Sister Morgan Variety

Image 4: Joseph Boudreaux Variety

Arbors

The American Heritage Dictionary defines arbor as a shady garden shelter19. According to some online sources, the concept of the arbors goes back as far as the ancient Egyptians, helping to create a shady resting place in the unforgiving hot dessert. There is recorded evidence of their popularity in Ancient Greek and Rome as well as through the Medieval period in Europe. In these references they speak of vining plants covering the arbors and they seem to add both beauty and functionality to the outdoor spaces. Newspapers in the New Orleans area also describe properties for sale in the mid to late 1800s with either grape, ivy, or rose arbors. In fact, there were a lot written of arbors in the New Orleans papers of the early 20th century extolling the virtue of the arbors to help hide unsightly fences as well as providing a nice shady and cool area to endure the summer heat of the semitropic New Orleans area.20 It also would make sense that especially in newly established, closely situated neighborhood yards of the early 20th century without many big trees, it would be just the answer for backyard privacy especially since folks probably spent more time outside then in. To note, the first house in the New Orleans area built with central air conditioning was Longue Vue House built in 194221. Thus in 1940, attic and window fans were the norm. According to the Sears advertisements of the day, a window fan could range between $32- $55. At the time, it looks like a bridge tender’s salary was around $25 per month. Of course, you could put down $5 to purchase, but I am sure it would easily be a year or so to pay just one fan off at a salary of $25 per month. Thus, even in the modern age of the 1940s, an arbor didn’t just hold value for its aesthetics, but also for its functionality.

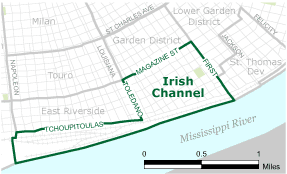

Life in the Irish Channel

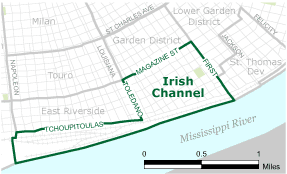

The Irish Channel is a name of an older working class New Orleans neighborhood south of the Garden District and adjacent to the Mississippi River, just upstream of the French Quarter. There apparently isn’t a definite origin of where the name came from, although the popular one is associated with the influx of Irish immigrants who came to New Orleans in 1830 to help dig the New Basin Canal and in turn, they “channeled” into the area where they settled.

Image 5: Irish Channel 22

At the time John Burns and his wife lived there, the area was essentially an 80-year-old neighborhood. Despite the name, there were other nationalities such as the Germans, Italians, and African Americans as well. The inhabitants primarily work around the Port of New Orleans in the 1900s, as was seen with John’s jobs prior to 1928. The area also garnered a reputation as being a tough area with a lot of gang rivalry that was more prevalent in the latter part of the 1800s. As with most of the city, the Irish Channel was predominantly Catholic and actually had 3 churches established in the early years for the different nationalities: St. Alphonsus for the Irish, St. Mary’s Assumption Church for the German, and Notre Dame de Bon Secours Church for the French. The churches were all consolidated in 1925 with St. Alphonsus becoming the Parish Church. It closed in 1979, but has been reopened as the St. Alphonsus Arts and Cultural Center. 23

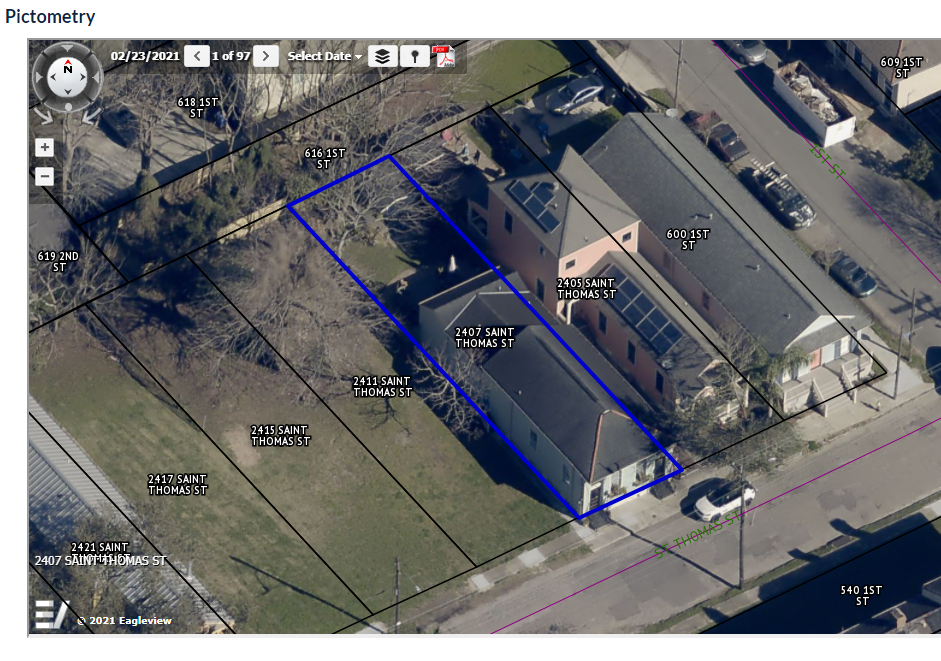

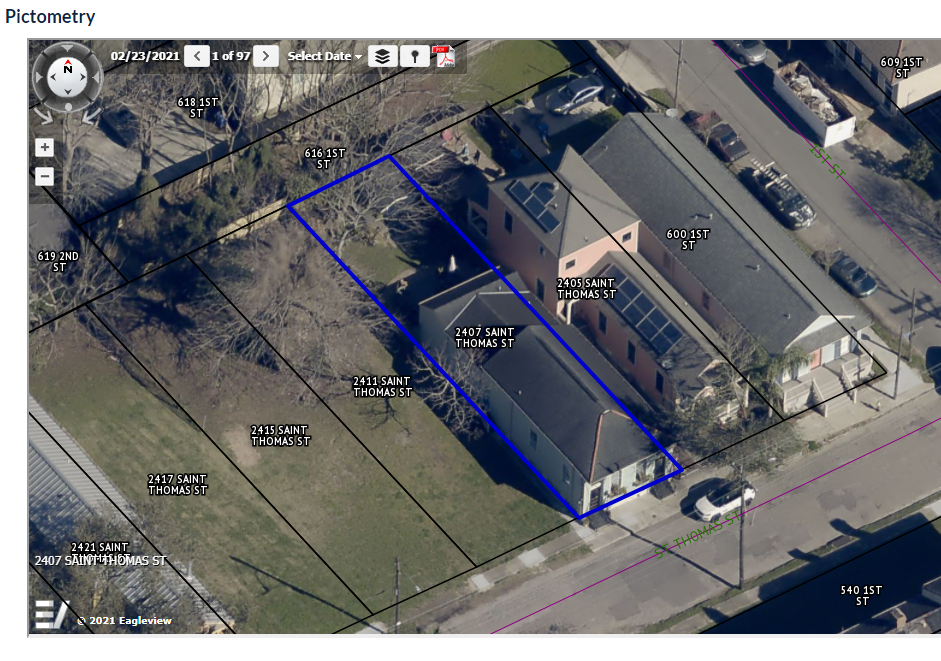

John Burns Sr. lived at the St. Thomas residence basically from (I’m guessing) 1914 till his death in 1947. The house number is listed as 2419 to 2409 during his lifetime and appears the twin shotgun was basically combined into one residence of 2407 sometime in the 1970s. Image 6 shows what this location looks like in the present day.

Image 6: Location of John Burn’s Irish Channel residence.24

From Image 7 we get a sense of what the back property’s dimensions were. Based on a measure of the current backyard, it is about 52 feet long by 28 feet wide, but in 1941, this house was a duplex, so one can only assume the yard may have possibly been split. The article list that the arbor was 28 by 16, which would match up with about half of the available yard in the backyard. The article also stated that “…behind it is a garden where there’s a peach tree that bears, fruit, a trellised rose vine that blooms the year ‘round a big chrysanthemum, shrub, a fig tree…” “Behind the garden is the shed and behind the shed the present pride of the Burns estate, an arbor of mirliton vines.” Evidentially the backyard was packed! As a side note, I am also speculating that the house looks to have been added onto, so I imagine there may have been more room in the early days.

Image 7: Lot John Burn’s Irish Channel residence.25

Per the rest of the article, we get a sense of how the arbor was constructed. Mr. Burns stated “I planted seven mirlitons last April right up against the fence there, opposite the shed and let them grow up as high as the top of the arbor now. Then I built out the arbor for about three feet, and put wires every three inches, and worked a half hour or an hour every day, spinning the new shoots around the wire, and when they went beyond that, I put on another three feet of arbor top, and spin the shoots along that, and so on till it covered the whole yard. That vine is a solid arbor 16 feet wide and 28 feet long now, and we can sit under the shade of it and enjoy ourselves.” This had to definitely be an impressive structure to behold. The amount of time to string the vines around astounds me, but I can feel his passion as I have easily spent 30 minutes retraining the direction of my vines. If a shed was approximately 6 feet tall and John Burns added another 6 feet (about 12 feet total) to it, it would also give a higher “ceiling” for the hot air to rise to. My mirliton arbor in Mobile is 8 feet wide by 24 feet long and 7 feet tall, so about half the size of Mr. Burns. I can only image the size and shade his provided. I am attaching a few pictures of mine so one might get a sense of how much shade this structure could provide, plus it must have been even more magnificent as the mirlitons hung down in the fall.

Image 8: Under the author’s shady mirliton arbor.

Image 9: The exterior of the author’s “unruly” mirliton arbor.

As a quick aside you might wonder how the Burns’ enjoyed their mirliton. Well according to Mrs. Burns, “when the mirlitons come -you see you scoop them out and stuff them with mirliton meat mixed with shrimp and sweet peppers and bread crumbs as a bit of bacon – that’s very good.” Mr. Burns also added that “Just frying a slice of mirliton with a slice of baloney sausage is mighty good too…I expect we’ll eat mirlitons this fall till we’re tired of them and maybe sell the rest. Not so bad, is it?”

Sadly, on Monday, April 14, 1947 at the age of 63, John Burns Sr. passed away. His wife Ellen lived on almost another 20 years and passed away on April 11, 1965. She apparently moved from the St. Thomas Street house the year after John died. At the time of his passing, John and Ellen had 5 children and 6 grandchildren. His funeral was held on Tuesday, April 15, 1947 at Leitz-Eagan Funeral Home which at the time was at 2241 Magazine St. Religious services followed at St. Alphonsus Catholic Church and he was interred at the St. Patrick No.1 Cemetery in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Image 10: John and Ethel’s Grave Stone26

Closing Thoughts

As I got into researching John Burns Sr., I felt a real admiration for his mirliton work. As I read about the Bridge Tender’s job, it occurred to me – having to take care of both activities on the road and water plus maintenance and safety had to be quite draining and stressful at times. I can imagine that when he got his arbor started it must have been a source of enjoyment and solitude away from the day-to-day operations. From what I can tell the house had to be around 850 square feet and with 5-7 people living there, things must have been often cramped. Utilizing the mirliton as an arbor is a brilliant idea that provided both beauty, functionality, sanctuary, and food to his large family. I think in many ways I could set up my arbor in a similar way and could easily utilize it as a nice space to relax and enjoy a cold beverage especially after yard work. Hopefully this will inspire others to set up a nice backyard arbor that can work their mirliton vines into the landscape. While John Burns Sr. had seven plants, my experience has been that one mature vine could be more than sufficient to provide cover in a small area. As we are seeing, the early 20th century mirliton growers were a creative bunch that didn’t simply just grow a plant, but utilized them in such a way that was both fun, functional, and committed to their hobby. I hope you are also inspired by the latest Pioneers in Louisiana Mirliton History, John Burns Sr.

Sources:

- Desutsch, Hermann B. “Orleanian Creates Beauty in a Mirliton Arbor.” New Orleans Item (New Orleans, LA) 18 September 1941, page 8 GenealogyBank

- 1900; Census Place: New Orleans Ward 1, Orleans, Louisiana; Page: 20; Enumeration District: 0001; FHL microfilm: 1240570

- 1910; Census Place: New Orleans Ward 1, Orleans, Louisiana; Roll: T624_519; Page: 10A; Enumeration District: 0001; FHL microfilm: 1374532

- 1930; Census Place: New Orleans, Orleans, Louisiana; Page: 8B; Enumeration District: 0193; FHL microfilm: 2340544

- Ancestry.com. U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005.

- 1920; Census Place: New Orleans Ward 11, Orleans, Louisiana; Roll: T625_622; Page: 1B; Enumeration District: 184

- http://nolaworkers.org/2018/12/17/the-1907-new-orleans-dockworkers-general-strike/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Orleans_dock_workers_and_unionization

- U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Charles L. Franck / Franck-Bertacci Photographers Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection – https://louisianadigitallibrary.org/islandora/object/hnoc-clf%3A1100

- New Orleans Item (New Orleans, LA) 18 July 1925, page 2 GenealogyBank

- Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA) 28 September 1925, page 4 GenealogyBank

- Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA) 14 November 1931, page 7 GenealogyBank

- Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA) 22 May 1932, page 10 GenealogyBank

- New Orleans Item (New Orleans, LA) 1 July 1934, page 4 GenealogyBank

- New Orleans Item (New Orleans, LA) 15 April 1947, page 5 GenealogyBank

- https://www.mirliton.org/photo/ed-landry-james-boutte-joseph-boudreaux-mirliton-varieties-dec-2010-chayote-sechium-edule/

- The American Heritage Dictionary, Dell Publishing, 1983, pg. 35.

- Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA) 11 March 1934, page 21 GenealogyBank

- https://wgno.com/news-with-a-twist/first-house-in-new-orleans-to-built-with-central-air-conditioning-still-operates-at-this-historic-landmark/

- https://www.datacenterresearch.org/pre-katrina/articles/IrishChannel.html

- https://readtheplaque.com/plaque/st-alphonsus-church

- Google. (n.d.). [Google Maps directions for driving from 2407 St. Thomas St, New Orleans, Louisiana]. Retrieved September 5, 2021, from https://www.google.com/maps/place/2409+St+Thomas+St,+New+Orleans,+LA+70130/@29.9236126,-90.0764497,3a,75y,10.91h,75.97t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1s0i31zWsT2KcsgVUY5ECu0g!2e0!7i13312!8i6656!4m5!3m4!1s0x8620a42a485e3ec1:0x9d258ff1c1881d79!8m2!3d29.9238154!4d-90.0764713

- https://beacon.schneidercorp.com/Application.aspx?AppID=979&LayerID=19792&PageTypeID=4&PageID=8665&KeyValue=2407-STTHOMASST

- U.S., Find a Grave Index, 1600s-Current [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

by David Hubbell | Aug 6, 2021 | How To, Mirliton

By Lance Hill

I remember the day I saw my first Mirliton vine wilting. I almost called 911. My first impulse was to water it, which I did, but it did not revive it that day. Miraculously, the next morning, the vine was in perfect shape.

Figure 1: Healthy and Happy Leaves orienting toward the sun and no sign of wilt.

Two Types of Wilt:

There are two types of wilting with mirlitons: temporary and permanent. They are different by degree, but while the temporary wilt can be fixed, the permanent one is a more serious problem. Knowing how to recognize a temporary wilt will help prevent it from getting worse.

Mirlitons are part of the cucurbit family along with cucumbers and melons. Cucurbits that have large, paper-thin leaves lose a great deal of moisture during hot weather—sometimes more quickly than the roots can replenish it. The moisture balance is also complicated by the plants’ shallow root structure. Mirlitons have two ingenious responses to excessive daytime heat: (1) they collapse their leaves so there is less surface exposure to direct sun (stress avoidance), and (2) they wait until the cooler nighttime to uptake more water into the leaves. It’s like humans fighting the heat by wearing a hat and shirt to reduce exposed skin surface and drinking water in the shade to rehydrate.

Temporary Wilt:

You can easily learn to recognize a temporary wilt (also called leaf flagging). The leaves will have lost some turgidity but not completely collapsed, as shown in the two photos. When you see this, you can use a soil sampler to sample the soil and see if it is too dry in the root zone (8″ down). You can also use your hands to feel how firm the leaves and stems (petioles) are. The video at the end of this post demonstrates the proper way to feel for a temporary wilt. The last thing you want to do if the plant is in a temporary wilt is to water the vine when it already has plenty of available soil moisture—you will flood the roots and cause root asphyxia, which leads to more wilting. Just wait until the next morning, and if the leaves have fully expanded and properly oriented toward the light, you have no problem. In fact, periodic wilting toughens leaves and gives them more protection from fungi.

Figure 2: Temporary Wilt (leaf flagging); Note that the leaves are no longer oriented toward the sun and are drooping, but not their stems. (photo by Kevin De Santiago)

Permanent Wilt:

Permanent wilting is caused by disease, pests, or overwatering that blocks the entire flow of water from the roots to the leaves. If you wait until morning and the leaves are still severely wilted, you have a serious problem. Unfortunately, there is no verified solution to these fungal toxins and insects like vine borers that block the uptake of water. August is the month when anthracnose will most likely attack the mirliton because of heat and frequent rains. There is a link below to how to diagnose anthracnose. But don’t worry: mirlitons can usually withstand a bout with anthracnose and still produce some fruit in the fall. In fact, the vine will acquire increased immunity from anthracnose each time it battles it.

.

Figure 3: Permanent Wilt. Note how even the leaf stems are drooping.

Figure 4: Bad news. This is the first sign in leaves of anthracnose. The wedge-shaped pattern of leaf death and the rifle shot hole are clear signs that the disease will soon spread to the stems and block the flow of water.

The reason leaves wilt or hold their shape is because of water pressure. It’s the same reason a limp balloon becomes firm when inflated with air. The key is what scientists call “turgor pressure.” Understanding the simple science of turgor pressure will equip you to identify the difference between temporary and permanent wilting. This short video explains turgor pressure. How to use your hands to test for a temporary wilt.

Read all about anthracnose here.

I

I

Recent Comments