Louisiana Mirliton Pioneers – Part I

Albert Smith, Sr. (1892-1963)

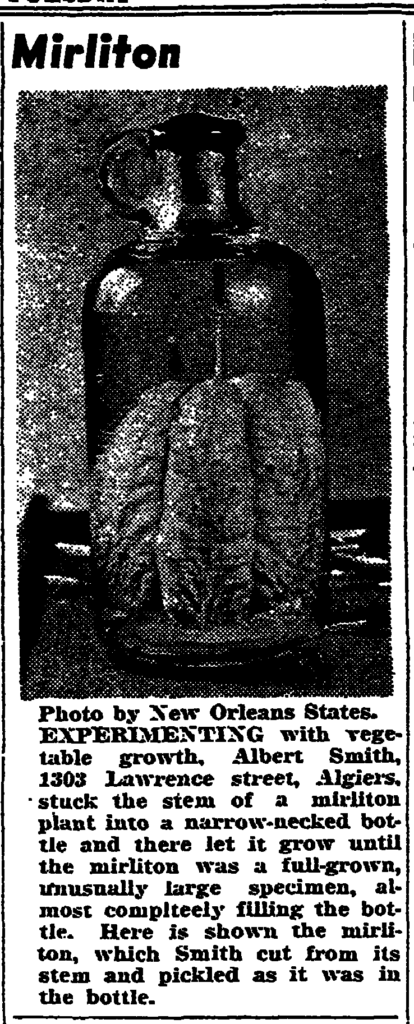

Most people have heard of a ship in a bottle or even a message in a bottle; but have you ever heard of a mirliton in a bottle? Well, if you were alive in New Orleans on December 5, 1939, you would have seen this incredible picture captured by the now defunct The New Orleans States newspaper.

Image 1: The New Orleans States1 Article

When I first came across it in my studies, I was struck with curiosity by a number of things: what kind of mirliton variety was this, what size and kind of jug was it growing in, and most importantly: who was Albert Smith, Sr.?

What Kind of Mirliton?

This question is probably the hardest to answer. The reason being is that mirliton comes in so many sizes, shapes, and colors and until Dr. Lance Hill and Mirliton.org started giving them “names” it was probably described by just that – size, shape, and color. Some things we can glean from the photo is that there is a good chance that this variety was probably light green to white. The reason I conclude this is that by looking at other black and white photos in publications from the 1920s-30s we can see how the this compares to those that have been identified as white or light green. The other thing we can learn is that the paper describes this as an “unusually large specimen”. The 1923 publication, The Chayote: its Culture and Uses2, by L. G. Hoover notes the ideal size for commercial use and home production is between 8 and 16 ounces. This falls pretty much in line with what I am familiar with from my own growing experience and with the work of Mirliton.org. The dimensions for these larger mirlitons can easily have a “width” of 4 inches and “height” of 6 inches. The mirliton also seems to have 5 deep furrows and more of a “snub nosed” top. Of course, in this case, the “snub nosed” top could perhaps have been formed due to growing in the jug, especially if it was growing just inside the opening. Oh, while its probably my imagination I feel like I can see some spininess on its surface, but before I go on, let’s look at the jug.

What Kind of Jug?

Based of off typical mirliton dimensions, even the largest of mirlitons would be dwarfed by a one-gallon jug. Additionally, we can surmise that this jug is clear. Based on what I could find online for vintage glass jugs and advertisements in the New Orleans papers of the day, I am guessing this size was a half-gallon that could have been used for common products such as syrup, vinegar, or even port wine. In any case, it would be perfect for just such an experiment, but why do it in the first place?

Fruit and Vegetables Grown in Bottles

A quick scan on histories of growing fruit or vegetables in a bottle reveal that it has been a practice for some time. The February 1930 edition of the magazine Popular Science features a photo of a Capt. John A. Gilman of the US Army Quartermaster Corp in Washington DC holding a watermelon inside a bottle (Popular Science – Google Books)3 and explains how it was done. Further searching reveals that a popular clear fruit brandy, Eau de Vie, which translates as “water of life”, often contains a whole pear inside the small necked bottle (technically this is called Eau de Vie de Poire). How long the practice of the pear in the bottle has been done is hard to say, but newspapers in the New Orleans area in the late 1930s ran several advertisements for Eau de Vie and some current purveyors of this brandy claim the practice of growing the fruit in a bottle has been done for centuries.4 Therefore, the idea of fruit and vegetables grown in a bottle could have easily been a popular idea floating around New Orleans area gardeners in the 1930s, especially if you were an inquisitive individual such as Albert Smith, Sr.

Albert Smith, Sr.

Image 2: Albert Smith Sr. possibly in the 1920s

On July 9, 1892, Albert Smith, Sr. was born in Quitman, Brooks County, Georgia near the Georgia/Florida border (close to Tallahassee) to William and Julie Smith. He married Ira Moore Thompson on November 17, 1915 in Brooks County as well5. According to Albert’s WWI Draft Card filled out on June 5, 1917, he was listed as living a little bit north of Quitman in Morven, Georgia6. At that time, we learn that he was employed as a Saw Mill Laborer and had one child. He is described as being of medium height with a slender build, with brown eyes and black hair. From the 1920 Census, we learn that Albert was still living in Brook County, GA in late January 19207, but by the 1930 Census, he was living in Algiers, Louisiana8. We also learn from this that his oldest daughter, Rose, who was born on September 14, 1921 was born in Louisiana. Thus, we can surmise that sometime between 1920 to 1921, that Albert, Ira, and their two children had moved to Louisiana.

So, what would bring this man and his young family from Georgia to Louisiana? Census records indicate that both his parents and wife’s parents were from Georgia, thus he appeared to have no family in Louisiana. Records also indicate that Albert had a railroad pension from the Southern Pacific Railroad Co.9, but the Southern Pacific’s most eastern destination along the Gulf Coast was New Orleans. It should be noted, that the Southern Railroad did leave from New Orleans to cover parts of the South and East coasts and it appears one of the short lines off of the main, traveled through Thomasville and Valdosta Georgia with Quitman right in its path. Additionally, sawmills had their own industrial railroads connecting to the other lines. Upon further research, it appears that the South Georgia Railway was built through Morven and appears to have fed the line going through Quitman. Thus, with Albert’s work at the sawmill, it would have put him in direct contact with the railroad on a daily basis for a time and as such he probably had several contacts with news from various parts of the route. While this was possibly the case, by 1920, he and Ira were both listed as laborers on a farm in Briggs, which was also in Brooks County. The average daily rate for a male farm worker across the country in 1919 was around $3.03 or maybe $0.38/hr10. Brooks County’s main agricultural product had been to grow cotton. Income levels in Georgia during the time appear to be slightly below the national average, so there is a high probability that their daily income was lower than this. So, what news could draw him to Algiers? In a recent NOLA.com article, I learned that the Southern Pacific Co. had a “…22-block-long railyard complex in Algiers. The facility once employed 4,000 workers and built steam locomotives and other rail parts… When in operation, Southern Pacific locomotives and railcars were transported by a barge ferry from downtown New Orleans to Algiers, where they were reconnected before moving on to western states.“11 Further research shows that the railroad had come to Algiers in 1852 and that this factory was built in 1920. Additionally, the following ad appeared in the May 7, 1920 edition of the Times-Picayune.:

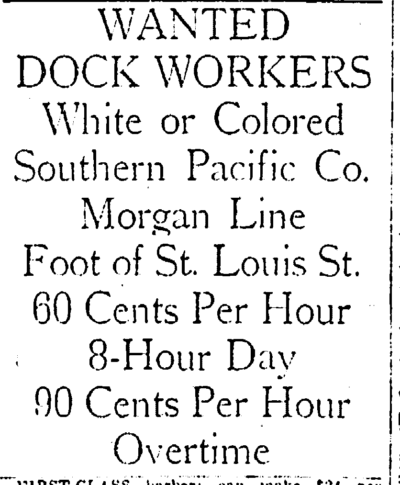

Image 3: Wanted Ad in 192012

Now, while this wasn’t the Algiers facility, it is interesting to note this hourly rate. There is a good chance that Albert could have easily seen the opportunity to possibly double his hourly wage and improve things for his family. Additionally, there was a recession from 1920-21, so there was probably even more incentive to move and look to improve one’s life. Regardless of what spurred the move, Albert appeared to have found a great opportunity with the Southern Pacific Co., which seemed to provide for him and his family through the rest of his working life and beyond.

Life in Algiers

Prior to moving to the Lawrence St. address listed in the caption, it looks Albert Smith and his young family were renting at 1723 Whitney Ave. in 1930. The best I can tell, they next moved to the Lawrence St. address, which they remained at until 1945-52. Image 4 shows what this location looks like in the present day.

Image 4: Location of Albert Smith’s Algiers residence13.

It should be noted that today there does not appear to be a 1303 Lawrence St., just 1301 and 1305. I am guessing it must have been renumbered at some point. It should also be noted that while Albert and his family lived here, the Greater New Orleans Bridge, known today as the Crescent City Connection, would not have been looming large behind them as it currently does, since it wasn’t built until 1958. Perhaps its impending construction is part of what led them to move one last time. Following these dates Albert and family moved to 1875 Whitney Ave. I am not sure where 1723 or 1875 Whitney were based off of the available information online. They either renumbered those properties as well or renamed that section of the road as L. B. Landry. It should also be noted that by then, Albert and Ira had a large family of twelve children; 7 daughters and 5 sons.

I was fortunate enough to correspond with one of Albert’s granddaughter, Monique Miles Logan, who through the help of her cousins queried two of Albert and Ira’s remaining daughters about his mirliton growing. The daughters remember that “…he always pickled them. He had a plentiful garden w/ okra, greens, mirlitons, tomatoes.” And that “ … (the) garden was like the Farmers Market because he shared with neighborhood.” Albert surely must have been a great gardener to be able to supply enough vegetables for his large family and the neighborhood.

As a quick aside on pickling mirliton, most recipes I have seen call for peeling, seeding and cutting the mirliton into strips. Albert’s method of pickling the whole mirliton seems very unique to me. Two of the pickled mirliton recipes I found from 1935 called for immersing the mirliton in a hot vinegar, salt, pepper (cayenne or green or Tabasco), and some pickling spices. These would be stoppered then allowed to “ripen” for 10 days indoors in a cool location. It would be interesting to try to replicate Albert’s experiment to see how one could possibly retrieve the mirliton to eat.

Sadly, on Tuesday, March 5, 196314, at the age of 70, Albert Smith Sr. passed away. His wife Ira had preceded him in death on Thursday, January 19, 196115. At the time of his passing, Albert left behind 12 children, 24 grandchildren, and 2 great grandchildren. He and Ira were buried at the Christian Social Cemetery in Gretna, Louisiana.

Image 5: Albert and Ira’s Grave Stone16

Closing Thoughts

As I got into researching Albert Smith, Sr., I felt a connection to him in the sense that he had some similar attributes to that of my late Grandfather, Lucien Robert. Both had 12 children, over 23 grandchildren, grew up in rural communities and settled in the “suburbs” of New Orleans, and had huge gardens that grew a variety of vegetables in their backyard, although in my Grandfather’s case he didn’t grow mirliton. I certainly would have loved to see the abundance that was generated from his gardens and learn from his years of mirliton growing experience, not to mention his creativity and ingenuity in getting a mirliton to grow inside a glass jug. So, can we ever figure out what variety of mirliton Albert grew? Sadly, probably not. Without a better picture or written description, it would all be just speculation and as all too many families living in the New Orleans area know, many of the Smith’s family photographs, records, and keepsakes were destroyed by the floodwaters of Katrina. Despite that I am thankful to those who preserved the old newspapers and also the fact that someone in 1939 decided to print the photo. For without them, I would never have known of or gotten to “meet” one of Louisiana Mirliton Pioneers, Albert Smith, Sr.

Special Thanks

To Monique Miles Logan, her Aunts, Cousins, and all of the Smith family for allowing me to share the story of their Father and Grandfather. Thank you also to Albert Smith, Sr. for the inspiration!

Sources:

- “Mirliton,” New Orleans States (New Orleans, LA) 5 December 1939, page 5, GenealogyBank

- L. G. Hoover, The Chayote: Its Culture and Uses, Circular 286, United States Department of Agriculture (Washington, D.C., September 28, 1923), https://archive.org/details/chayoteitscultur286hoov/page/n1

- Popular Science, Feb 1930, pg. 60, Vol. 116, No. 2.

- Poire Williams – Gastro Obscura (atlasobscura.com)

- Ancestry.com. Georgia, U.S., Marriage Records From Select Counties, 1828-1978 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013. Original data: County Marriage Records, 1828–1978. The Georgia Archives, Morrow, Georgia.

- Ancestry.com. U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005.

- 1920; Census Place: Briggs, Brooks, Georgia; Roll: T625_237; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 47

- 1930; Census Place: New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana; Page: 6A; Enumeration District: 0256; FHL microfilm: 2340547

- United States. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (1939). Monthly labor review. Washington: G.P.O.

- The National Archives at Atlanta; Morrow, Georgia; Records of the Railroad Retirement Board, 1934 – 1987; Record Group Number: 184.

- “Algiers Point’s empty tract could be developed if contaminated soil is removed”, NOLA.COM, (New Orleans) by Mark Schleifstein, May 6, 2020.

- Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA) 7 May 1920, page 18, GenealogyBank

- Google. (n.d.). [Google Maps directions for driving from 1303 Lawrence St, Algiers, Louisiana]. Retrieved May 13, 2021, from https://www.google.com/maps/place/1303+Lawrence+St,+New+Orleans,+LA+70114/@29.9391452,-90.0433388,3a,75y,199.8h,84.53t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sVCCZOql-vh2UJaxdtwiBew!2e0!7i16384!8i8192!4m5!3m4!1s0x8620a651e0e21fdb:0xaa415c29ebd08d64!8m2!3d29.9388922!4d-90.0433527

- Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA) 8 March 1963, page 2 GenealogyBank

- Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA) 22 January 1961, page 10 GenealogyBank

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/157156887/albert-smith

Recent Comments