by Lance Hill | Feb 28, 2024 | How To, Mirliton

If you felt feverish and wanted to check your temperature, you wouldn’t guess; you would get a thermometer and take your temperature. Your garden soil is no different, and we now have a way to determine exactly how much soil moisture your mirliton has available: the soil sampler.

If you felt feverish and wanted to check your temperature, you wouldn’t guess; you would get a thermometer and take your temperature. Your garden soil is no different, and we now have a way to determine exactly how much soil moisture your mirliton has available: the soil sampler.

The soil sampler is the simplest way to see how much moisture your mirliton roots are getting. It’s the quickest and most inexpensive way to determine if you have overwatered or underwatered your vine. Knowing what is happening several inches below the surface is even more important during droughts — many growers lost their vines during the heatwaves in 2023 and 2024 because the soil was starved of moisture.

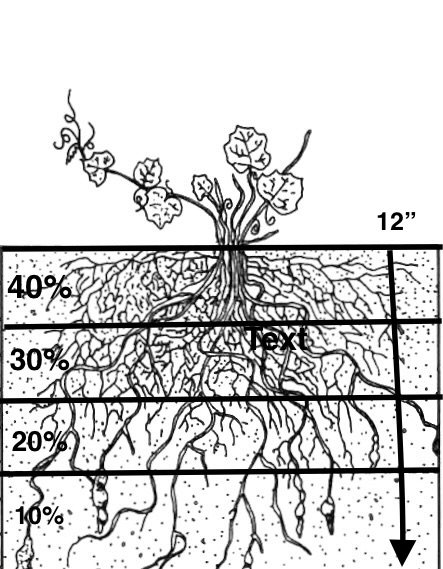

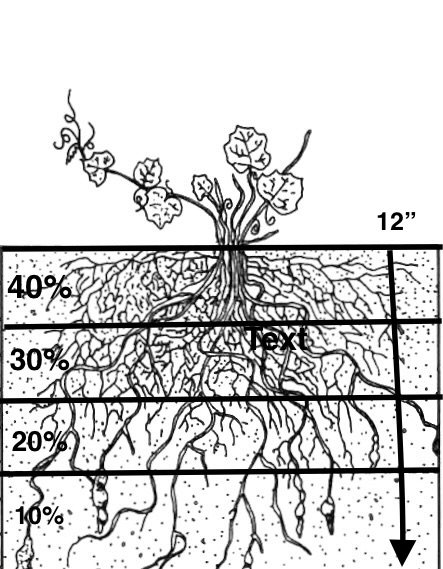

The “knuckle” method of sticking your finger into the soil only tells you what the soil moisture is near the surface; that method does not work with mirlitons because the roots extend downward 8″. Electric meters are also ineffective because they measure electrical conductivity–not soil moisture. The only way to know the available soil moisture beneath your mirliton is to see and touch it, and that’s exactly what a soil sampler allows you to do. Mirliton growers in Brazil have used this method for years.

James Leblanc demonstrates how to take a sample and check moisture levels at all root zone levels. First, pull a core sample and then examine the soil by pressing down on it in the sampler at intervals of about every inch. Feel for moisture and how it compresses. That will indicate the amount of moisture present at each level. If it’s bone dry and crumbly, it needs more watering. If it’s muddy–it has too much. After a while, you will be able to easily take a reading by touch and sight. The soil will generally be moist at the surface level, and should even out as you go down about 8 inches.

See how James does it here

Buy a soil sampler here..

Mirliton rootzone:

by Lance Hill | Feb 18, 2024 | How To, Mirliton

There are no scientific studies on cross-pollination in mirlliton varieties, so we can’t speak with any certainty about the chances of cross-pollination. Mirlitons are self-pollinating plants and are primarily pollinated by bees. Honey bees are systematic foragers; they will focus on one plant until they have collected all the nectar. That means they are less likely to carry pollen from another plant, thus reducing the risk of cross-pollination.

Because of this, generally, you can grow two different varieties with little risk of cross-pollination. If you grow only one variety at a time, you will have even less risk. But if you want to ensure that the offspring of a plant will be true-to-type, there is a simple way to do that: controlled pollination.

Using controlled pollination will guarantee that the specific fruit you picked from your vine will grow the same variety. Click here to see how to do it.

by Lance Hill | Oct 30, 2023 | How To, Mirliton

Frost Protection

There is a possibility of a damaging frost whenever the temperature drops below 38 degrees. You can protect your mirliton with either a minimum or maximum plan.

Minimum plan: Tent the vine the day before with a tarp or 4mil plastic cover. A FEMA tarp will work well. Weight down the edges of the tarp with bricks (you are trying to trap the heat from the soil inside the enclosure). This will raise the temperature a few degrees and may avert the frost.

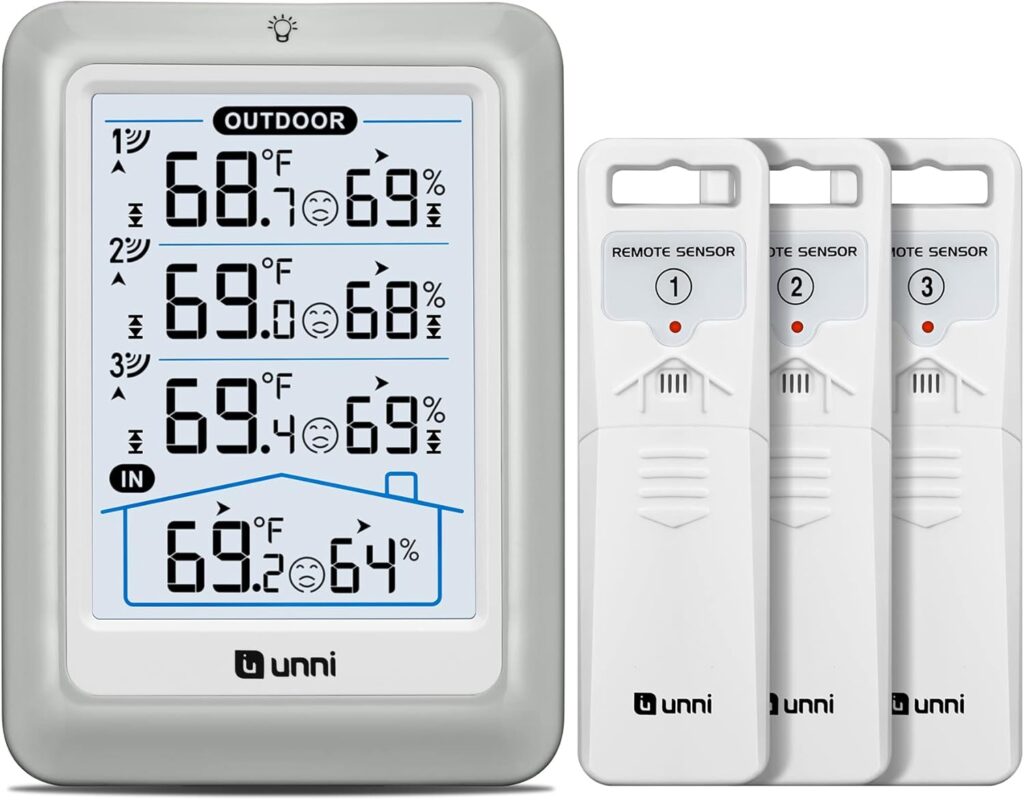

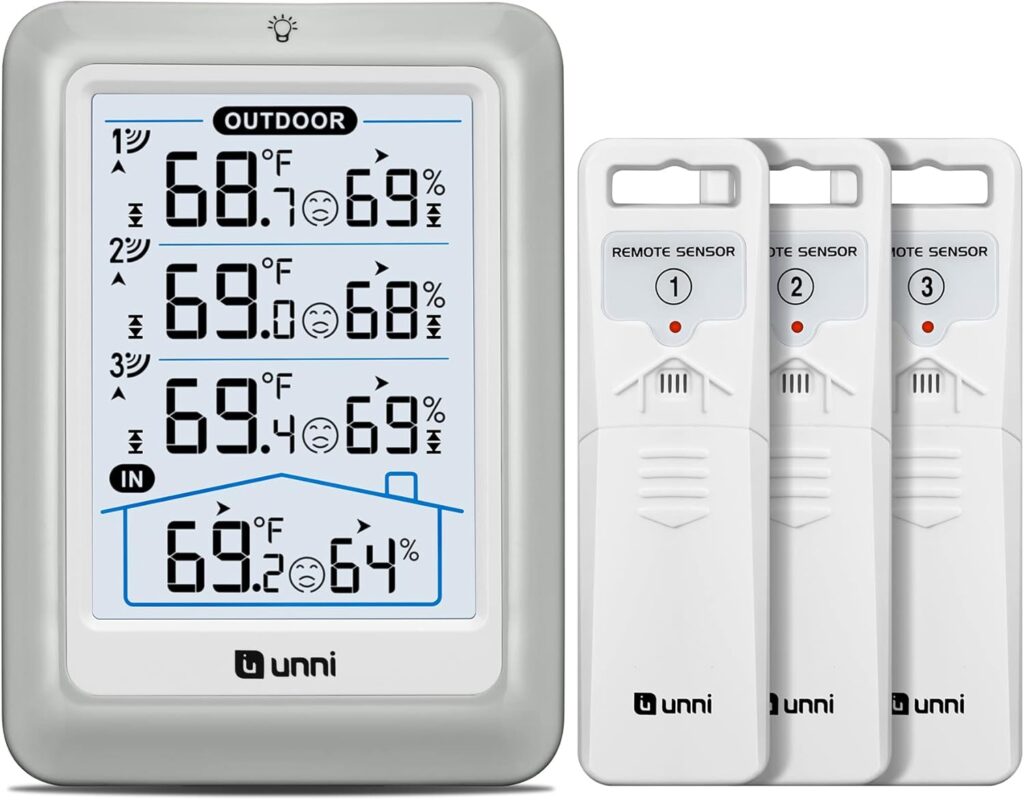

Maximum plan: Add heat to the tent. You will need an extension cord and a small space heater. A space heater will raise the tent’s internal temperature several degrees, which will protect the vine if temperatures dip to 32 degrees. There are also portable gas heaters. Buy a remote thermometer and place the sending unit in the tent enclosure and you will be able to see exactly what the internal temperature is. Remote thermometers will permit you to see what the temperature is in the tented trellis from the comfort of your home. They are the best defense against a freeze–and cost only

$20. Buy it here.

by Lance Hill | Oct 17, 2023 | How To, Mirliton

The Louisiana Mirliton Two-Step

Because of increased extreme weather events like Heat Domes and frequent hurricanes, we need to think entirely differently about when and how to grow mirlitons. We have two chances at a mirliton crop: Spring and Fall. We need to especially take advantage of our cool months, October through May.

Step One

Plant your mirliton seed or container plant in the fall and build a trellis for the vine to grow on all winter. When necessary, temporarily cover it with 4-mil plastic and warm it with a portable heater to protect it on frost/freeze days. By the following spring, the vine will have a large canopy to support flowering–and you will get a spring crop.

Step Two

To help your vine get through the summer, use the same trellis to support a 30% shade cloth to shade the vine from June through August, if necessary. That will give you a a good chance at another crop in the Fall

10’ X 25’ 4-mil plastic sheets

Space Heater

Shade Cloth

Remote Thermometer for Enclosure

by Lance Hill | Apr 30, 2023 | How To, Mirliton

Sometimes bees and other pollinators are not doing their job, and you want to ensure that your female flowers are pollinated. Gardeners are often advised to remove male flowers and apply them to the females. But this destroys the male nectar, which attracts pollinators. Instead, the simplest way is to hand-pollinate with a slender artist’s brush with dark horse hair bristles (the nylon brushes won’t work). The bristles make it clear that you have collected yellow pollen from the males. Using a brush means you do not destroy the males and can return to them for additional pollen.

Click here to see how to do it.

by Lance Hill | Apr 9, 2023 | How To, Mirliton

Mirliton is the name people gave the chayote (Sechuim edule) when it first arrived in Louisiana. Chayote is the main species and there are many subspecies (subvarieties) around the world with different names. They are what botanists call a “landrace.” Landraces are domesticated plants that developed over time and adapted to their natural environment and are not the product of human manipulation–such as plant breeding or modern genetic science. Haitians brought the first mirlitons to Louisiana over two centuries ago and that landrace thrived because it was adapted to our altitude, climate, pests, and diseases.

Since the Louisiana variety has never been analyzed genetically, we have had to use the fruit appearance to classify it and its subvarieties. The Louisiana mirliton landrace has distinctive fruit traits (morphology); they are large, slightly pear or egg-shaped, with smooth skin, longitudinal furrows (though a few may be unfurrowed), and either green or white. Over the years other varieties were probably introduced from Mexico and Central America and interbred with the Louisiana landrace. The resulting landrace was what generations of Lousianians simply called “mirlitons.” And for most of the last two centuries, there was only one variety.

Then things changed. Hurricane Katrina wiped out almost all the mirlitons in New Orleans, so I began to search for growers of our Louisiana landrace to replace the New Orleans ones. I eventually found many growers in rural areas and when I did, I would name the mirliton after the grower so that we could track and preserve it.

I soon noticed differences within Louisiana mirlitons–there were clearly different subvarieties in the landrace. Mirlitons were more complex than we thought. I decided to classify the subvarieties by fruit morphology and then interview the growers to determine the strain’s history. If it were a unique variety, we would name the variety so we could track and preserve it. That’s how “named varieties” came to be.

We have reached the point in 2024 where we have identified most of the Louisiana subspecies. To simplify matters, from this point forward, we will classify mirlitons into three categories for purposes of discussion on our Mirliton.Org Facebook group:

- Certified Heirloom Mirliton: A variety that was submitted to Mirliton.Org for visual review and met all the heirloom criteria. Anyone can submit photographs of their variety for review at no cost. If we certify it, you can say on the Mirliton.Org Facebook group that you are growing a “certified heirloom mirliton.” Submit photos to lance@mirliton.org or at the Mirliton.Org Facebook group. We maintain a public list of all certified heirlooms that you can refer people to verify that you are growing a certified variety.

- Certified Named Heirloom Mirliton: These are varieties that were submitted to Mirliton.org in the past that met all the requirements and were sufficiently unique that Mirliton.Org named them for tracking and preservation purposes.

- Louisiana Heirloom Mirliton: These are the varieties grown along the Gulf Coast south that were obtained from an unknown source (a local farmer, a seed store, etc.), and the grower sincerely believes they are Louisiana heirlooms. If you are growing one of these uncertified varieties, you can simply say it’s an “heirloom mirliton” or “Louisiana heirloom.”

There are currently 14 Certified Named Heirloom Varieties:

Ervin Crawford

Ishreal Thibodeaux

Boudreaux-Robert

Blacklege

Papa Sylvest

Bogalusa whites

Chauvin-Rister

Miss Clara

Remondet-Perque

Joseph Boudreaux

Bebe Leblanc

Maurin

Jody Coyne

Dupuy-Prejean

Why is it important to continue tracking heirlooms? Beginning in 2020, several large grocery store chains began importing chayote (mirlitons) that looked exactly like our heirloom varieties. People began buying them, using them as seeds, and growing mirlitons indistinguishable from our heirloom varieties. The problem is that imported chayote may carry a seed-transmissible virus that can destroy our heirlooms. It’s called Chayote Mosaic Virus (ChMv), which devastated crops in other countries. Recent research has also discovered new strains of anthracnose in Brazilian chayote that can be transmitted inside the fruit.

We created the certification process to help preserve and popularize the Louisiana heirloom variety. We recommend that the best way to accomplish this is to use only certified heirloom seeds.

If you felt feverish and wanted to check your temperature, you wouldn’t guess; you would get a thermometer and take your temperature. Your garden soil is no different, and we now have a way to determine exactly how much soil moisture your mirliton has available: the soil sampler.

If you felt feverish and wanted to check your temperature, you wouldn’t guess; you would get a thermometer and take your temperature. Your garden soil is no different, and we now have a way to determine exactly how much soil moisture your mirliton has available: the soil sampler.

Recent Comments