Mirliton How-To Tips

Search tips by keyword:

How To Grow A New Mirliton Seed

Sprouted Mirliton

You can ground-plant a fall mirliton sprout as late as October, and a spring sprout as late as June. The June planting will have to be initially shaded. See here. Outside these two windows of opportunity, you will have to plant the sprout in a 3-gallon container until you transplant it into the ground. (see below how to container and trellis it). Get the plant growing in a container as soon as possible–it will create a strong root ball for transplanting and it may even produce a spring crop!

1. Mirlitons should be sprouted (germinated) before planting. If your mirliton has not sprouted, (fig. 1) place it horizontally on top of the refrigerator– the warmest part of your house. If it does not sprout within two weeks, you should speed up the process by “incubating” the sprout (explained here)

Fig. 1. Unsprouted mirlitons.

2. If your mirliton has already begun to sprout (tongue sticking out) (fig. 2), you are ready to overwinter it to help it develop a root ball.

Fig. 2. Sprout first emerges (above) and shoots extending (below). These are ready to plant.

3. Over-wintering: Once your mirliton is sprouted, you plant the whole fruit at a 45-degree angle about 2/3 of the way down with the sprouting end down in a 3-gallon container filled with good potting soil (fig. 3). Water thoroughly the first time. Mirlitons don’t need much water during the overwintering. Here’s how to use a bamboo skewer to test soil moisture. Or you lift the container slightly every few days to gauge if the soil is drying out, and only water if it is noticeably light. David Hubbell has an excellent video on overwintering a mirliton here.

Fig. 3. Sprout planted “sprouting end down” at 45-degree angle with about 2/3 underground in a 3-gallon container.

4. Trellising: Use a 24” – 36″ tomato cage as a trellis. Let it climb the cage, but you can prune to keep it compact—a plant in a 3-gallon container can last for up to a year. When the weather permits, keep it outside in full sun and bring it in when there is the potential for a frost or freeze. The goal is to develop a good root ball. When you transplant it into the ground in the spring, the vine can be unwound from the tomato cage, and the canopy can be attached to your garden trellis (see below images).

Mirlitons trellised on tomato cages.

5. Give the container plant as much sun as possible, preferably outside, and bring it in when temperatures drop below 42 °. If you have rodent problems, protect it with a wire cage:

Steel wire squirrel protection. Make the mesh guard at least 3′ high to protect new growth. Wire mesh can also be used with ground plantings to prevent rodents from digging up the vine.

6. Transplanting: When the possibility of a spring frost passes, you can transplant it into the ground. Harden it off for a few days before transplanting into full sun. If your container plant is well-developed, you can even get a small spring crop! See the Quick Guide for instructions on building a grow site and general procedures for watering, fertilization, shading, and plant pests and diseases. Join the national mirliton gardeners Facebook Group to post questions and follow the progress of other Mirliton gardeners here.

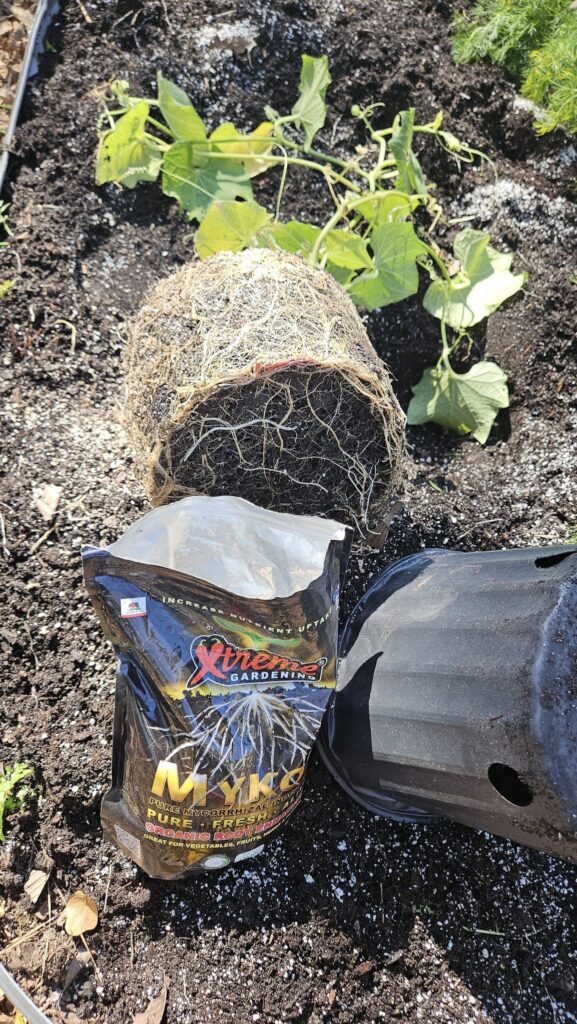

Well-developed root ball on a 3-gallon plant ready to transplant into the ground.

Squirrel Repeller That Works

Meet The Squirrelator

Well, it doesn’t eliminate them, but it does scare them off, and anyone who has ever grown mirlitons knows that squirrels eat the vine endings and steal the fruit. What to do? A wise old extension agent in Mississippi once said, “If there are 100 cures for something, probably none of them work.” I tried a 100 for squirrels: CDs, noise repellers, and cayenne on the bird seed (the Cajun squirrels loved it). None of them worked. This motion-activated sprinkler shoots a short burst of water in an arc over your vine.

David Hubbell tested it for the last two years– complete with a game camera that he used to monitor it. The thing works. It is based on the simple principle: Did you ever see a squirrel dancing in the rain?

They work for other crops and will also keep your neighbors from pilfering your garden at night.

It’s available at most online stores, but here’s the Amazon link.

(If you are trying to protect a container plant or a new small plant, a wire mesh guard will also work.)

Wire mesh guard for protection against squirrels.

Sprinklers Are Effective Frost Protection for Mirlitons

Mirliton vine the day after a frost that was protected with a rotary sprinkler. The vine is healthy and ready to produce.

A damaged portion of the same vine that was beyond the reach of the sprinkler.

No one wants to nurse a mirliton for months through droughts, floods, and hurricanes, just to have Jack Frost arrive and kill all your flowers before they can fruit. Sprinklers are the most effective, simplest, and least expensive way to protect mirlitons from an early frost. Moreover, hot weather is the ideal time to set up your sprinkler and adjust it because you don’t want to be running around getting soaked in freezing weather.

Horticulturalists in the South seldom recommend sprinklers because most home gardeners grow soft-tissue vegetables that ripen long beroe the threat of fall frost. But we can find excellent advice from Canadian experts who have perfected the sprinkler systems to protect strawberries from early Sring frosts. We used their experience to design a simple and effective defense against temperatures down to 38 degrees in the fall.

Spraying water on a plant to warm it up seems counter-intuitive, but it works because of a simple principle; when water evaporates from the leaves, it transfers heat into the plant. And when changes to ice on the surface of a plant, it will add heat to that plant. Frankly, the science baffles me, but if you want to know more about it, click here for the Canadian study. For our purposes, the sprinkler frost-defense steps are simple:

Sprinkler Set Up:

1. Place a rotary sprinkler with a metal spike securely on the ground and connect a garden hose to it.

2. Turn the hose on and adjust the sprinkler and mount so that the stream covers the entire vine. Any sprinkler will do, but it’s best to use an impulse sprinkler that can spray a 180-degree arc so you can cover the entire vine. You may have to angle it up.

3. Secure the metal spike so that it does not move when the water is left on for several hours.

When and How to Use the Sprinkler system:

1. Watch the temperature forecast. If the temperature is predicted to go below 38 degrees that night, turn the sprinkler on at sunset and make sure it covers the entire vine.

2. Normally, the coldest part of the night is 4:00-6:00 a.m, so you can turn off the sprinkler after sunrise if the forecast is for temperatures above 40 degrees during the day.

That’s it. We have tested this system on mirlitons for over 10 years and every time it has worked and saved the vines. In 2012, Leo Jones in Harvey, Louisiana used the sprinkler for only part of his vine– it lived while the rest of the vine died (photo above). In 2019, Renee Lapelrolie also used sprinkler heads on only part of her vine, and again, only the protected portion survived (photo below). Not only can the sprinkler protect the vine in the fall, but during a mild winter, it can be used instead to keep the vine alive for a Spring crop.

Buying a sprinkler:

The Rain Bird impulse sprinkler is the best sprinkler head. You can buy it with the reinforced stake and it can cover a vine 40 feet long. There are other brands available, but the Rain Bird is the only one I have had experience with.

Rain Bird Sprinkler Head With Metal Spike Base click here.

How to Adjust Rain Bird click here.

Canadian strawberry frost-protection instruction publication, click here.

Rene Laperolie’s mirliton vine after the 2019 frost. In the foreground, the sprinkler protected the vine. In the background, the unprotected vine was damaged.

Managing Vine Borers in Mirlitons (chayote)

I have researched how to manage squash vine borers and there is remarkably little scientific research that will help the home gardener. Big commercial growers use a chemical drench, but that’s no help for organic gardeners. I have heard of wrapping the base of plants with aluminum foil. Maybe that works, but I have not found any rigorously controlled studies of the methods.

Physical barriers and BT (Bacillus thuringiensis) appear to be the most effective management methods. Barriers such as row covers in the spring will help prevent the moths from laying eggs. Regular foliar spraying of BT (Bacillus thuringiensis) appears to be the most effective way to manage squash vine borers. There is persuasive research that BT works on cucurbits like mirlitons (chayote). Start spraying the vines early in the spring and continue throughout the season (don’t mix with oils because they can kill the vine in hot weather).

Some people inject the BT into the vine with syringes, but this will not work because larvae don’t consume BT and it will only kill the larvae if it reaches their gut.

Click here for a short overview of vine borers and how to manage them.

Click here for the best article I found on BT for managing vine borers.

Click here to read about how it is safe for humans to use on crops.

How to Identify and Control Leaffooted Stink Bugs on Mirlitons (chayote)

Leaffooted stink bugs have invaded our mirliton gardens and orchards. They feed on flowers and fruit, killing flowers and injecting enzymes and diseases into the fruits that ruin the flavors or bruise them. And, yes, they stink.

There are several leaffooted stink bug species in the Gulf Coast South, but the principal culprit is a new arrival Leptoglossus zonatus (Dallas), widely known as the “western leaffooted bug”. They are with us year-round and overwinter in weeds and tree bark. They emerge in the spring as “nymphs” (immature bugs) and go through five stages called instars. We will concentrate on two of the stages that gardeners are most likely to see on their vines: nymphs and mature bugs.

How to Identify:

Identifying leaffooted bugs is tricky since they look almost identical to assassin bugs, which are beneficial insects that eat bad bugs and don’t damage plants. Because they are physically similar, sometimes people try to distinguish them based on the different markings of the two species. That will work for mature stink bugs, but markings are not always useful for nymphs because they don’t appear in all instars. For example, the characteristic leaf-like “flared” back legs don’t appear in all stages of a leaffooted bug’s life (see the two photos below of nymphs with no flared legs on a mirliton fruit and flowers). A simpler and more reliable way to identify stink bugs is by behavior:

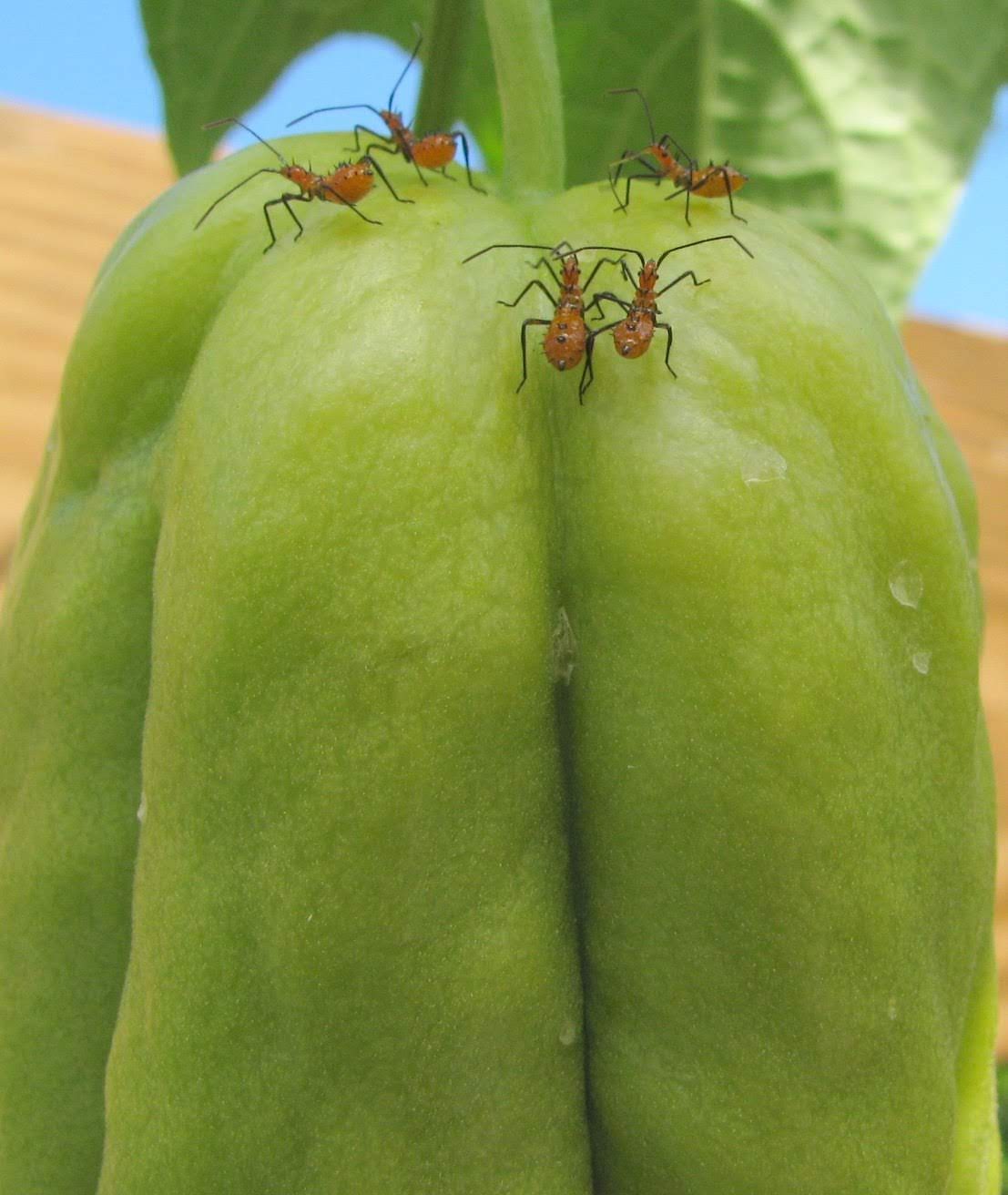

Nymph stage: For most of the growing season, stink bug nymphs are easily identified by their aggregating (swarming) behavior. They like to aggregate into small gangs and search for young flowers and immature fruit. In contrast, assassin bugs are solitary hunters, even as nymphs, and won’t be found in gangs. So don’t t worry about markings; if they behave like a gang, then they are stink bugs. You can control them at this early stage with regular spraying throughout the growing season with insecticidal soap or organic pesticides such as Bee Safe Organicide that won’t harm bees.

Immature nymph leaffooted bugs in characteristic swarming behavior. Note that at this stage, they don’t have the flared back legs.

Stink bug nymph feeding on immature flowers (also, no flared back legs)

Stink bug damage to young mirliton fruit. Note exudate emerging on top right in a bubble.

Mature stage. Adults can’t be sprayed away; they have a hard exoskeletal structure that protects them from topical insecticides. They are also solitary foragers like assassin bugs, but they are easily identified because they are vegetarians. In contrast, assassin bugs only eat other bugs while leaffooted bugs feed on flowers and fruits. They have to be removed by hand by picking them off by hand, sucking them up with a portable vacuum, or catching them with a butterfly net.

I prefer the hand vacuum (with a homemade 1/2 inch diameter PVC extension—see below) because stink bugs are highly aware and will instantly dash away at the sight of a large extension. Plus, you are less likely to damage flowers. The contents of the vacuum can be emptied into a pail of water with insecticide. Leaffooted bugs and assassin bugs are quick and elusive and difficult to identify as adults. If you accidentally removed an assassin bug, it will not hurt the species since they forage everywhere, unlike leaffooted bugs that target your vegetables and fruits.

Mature leaffooted bug. Note white mark across the back and the well-developed flared “leaves” on the back legs.

Monitor For Stinkbugs Daily:

The key to managing pests is knowing which ones are on your vine because early intervention is critical. Closely scout your vine every day, top and bottoms of leaves, and use sticky yellow insect traps to collect specimens. Click here for sticky traps.

Click here for an excellent recently updated fact sheet on Leptoglossus zonatus (Dallas)

The Dewalt 20v. portable vacuum has the power to vacuum up large bugs and can be used for household and automotive cleaning. An accessory kit is available and that will allow you to fit it with a 1/2-inch PVC pipe extension.

Identifying and Contolling Powdery Mildew in Mirlitons

Powdery Mildew on a leaf in the early stages of the infection. The best time to diagnose powdery mildew is in the early stage on mostly green leaves. It starts as irregular pale yellow blotches that combine until the whole leaf is yellow.

Powdery mildew is a troublesome plant disease, but thankfully, it is never lethal. It’s largely a Spring disease because it thrives in cool, damp weather, so it’s the first disease you will see in the mirliton growth cycle. The good news is that there’s an effective organic fungicide that manages the disease.

The signs of powdery mildew on mirlitons are not the same as on most other plants. Gardeners are often advised to look for a white powder on the leaf surface. But that seldom appears on mirliton leaves–probably because the spring rains wash off the leaves. The most obvious signs will be yellowing, dead leaves, and by that time, the infection will have advanced. And yellowing leaves can also be caused by overwatering.

So, what’s the best way to spot the disease? The most accurate way to identify powdery mildew in its early stages is to examine the seemingly healthy green leaves near yellowing ones. The early signs of mildew are irregular, faded yellow blotches like those in the photo above. That is the fungus forming little colonies that will eventually turn into bright yellow leaves.

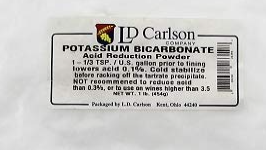

If you find signs of the disease, there is a highly effective organic fungicide that can control it: potassium bicarbonate. It can completely eradicate the disease in three weeks and works on downy mildew as well.

We recommend L.D. Carlson’s potassium bicarbonate because the manufacturer has verified with a Certificate of Authority (COA) that it is at least 99.5% pure. It’s generally sold in one-pound quantities, which is more than you will need, but it has a long shelf life, and you can share it with other growers. Click here to order online.

L.D. Carlson’s potassium bicarbonate.

If you are using a 99.5% pure potassium bicarbonate product, mix one tablespoon with a gallon of water and shake vigorously. Then spray only in the evening and thoroughly wet the tops and bottoms of all leaves. Apply once a week for three weeks until there are no signs of early infection (faded yellow blotches on green leaves).

For a more thorough article on powdery mildew and mirlitons, see my paper here.

Making Spring Mirlitons Sprout

Sprouting mirliton.

We occasionally get a Spring mirliton crop and decide to gift or sell them to others to grow. You could plant them in small containers and sell them that way, but that would mean that potential growers would have to transplant them into the ground during the full heat of the summer. That would be risky. That’s why we recommend that growers sell their fruit as sprouts as soon as possible after picking them. Sprouts can be safely planted in May-June with a simple shade technique (click here). So how do you expedite sprouting?

Mirlitons sprout (germinate) in response to warm weather. Joseph Boudreaux taught me the simple technique for incubating mirlitons in May: Place them in a warm place outside and they’ll sprout within 10-14 days. It’s best to place them away from the direct sun and inside a container such as a milk crate where varmints can’t get them (squirrels, possums, and rats). As soon as they begin to sprout, you can assure people that they are viable seeds and ready to plant.

How To Read Mirliton Leaves for Vine Watering Needs

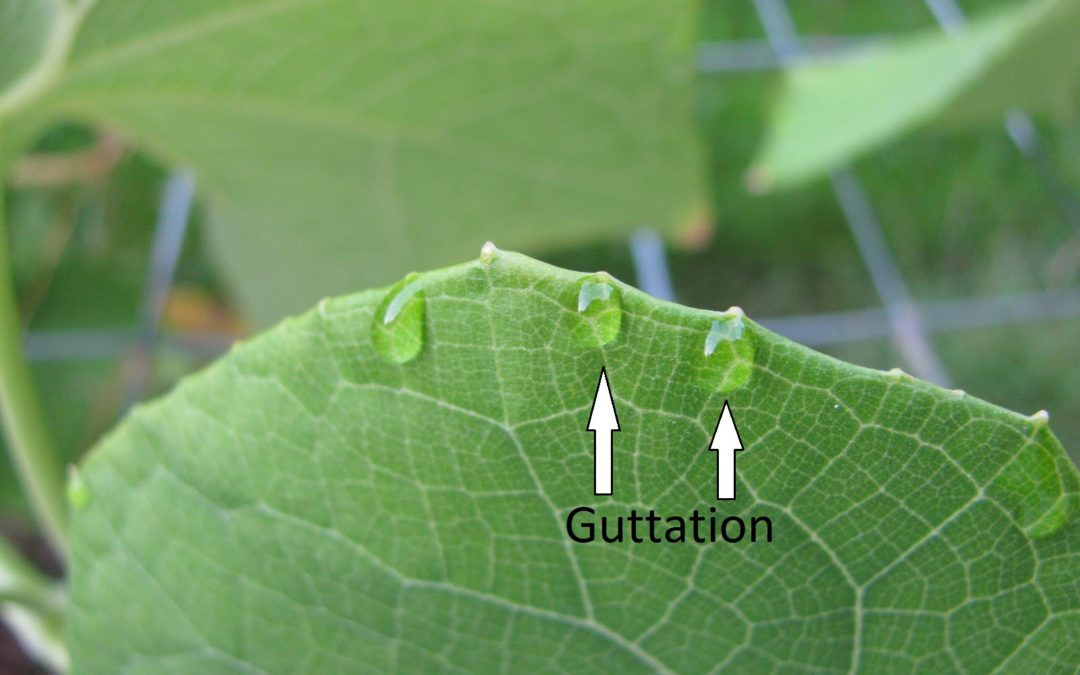

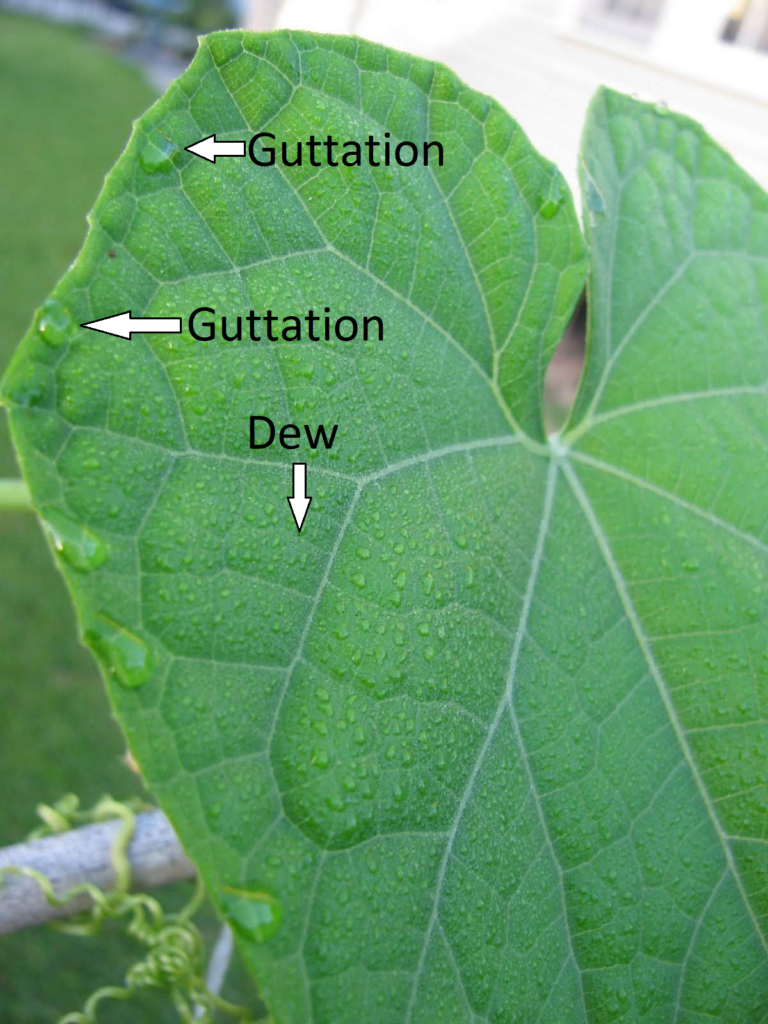

Guttation forming on leaf tips and edges

Your mirliton will tell you every morning how much water its roots are accessing. It is called “guttation.” If there is more than adequate soil moisture available at night, mirlitons will send the excess to the leaves where it will be visible in large droplets on the margins of the leaves. The water exudes from glands at the tip of the leaves. Guttation means the plant has more than enough water; if you don’t see guttation for several days, then it’s probably time to water. Click here for a link to instructional photos of guttation and how to read it (click on each photo for explanations).

Watering Mirlitons

Watering Mirlitons

I could have titled this “How To Water Your Mirliton” but that would be like asking, “How To Care for a Child.” There’s no single answer because each child is different and has different needs at different times in their life. Plants are the same. So this is a set of guidelines instead of rules for watering mirlitons during their three distinct stages in their life cycle.

It used to be said that mirlitons “take care of themselves” and need little care; the increase in hurricanes, floods, and intensive rain days means that is no longer true. Now they need intensive care. No watering technique can remedy a flawed plant site. Mirlitons need quickly draining, well-aerated soil. That means you may have to install drainage (ditches, French drains) in your ground planting; in raised beds, you need lateral exit routes for excess rain, such as side holes or subsurface corrugated pipe. Rapid and wide fluctuations in soil moisture content in your raised bed can stunt growth and hinder flowering and fruiting. These guidelines will generally apply to both planting methods.

Steps to take Before You ever Turn on the Hose:

Get a rain gauge. Place it next to your vine and check it daily. The weather person has no idea how much it rained in your yard—you need to know it for your vine’s health.

Don’t guess about the vine’s water needs. The soil and the leaves will tell you exactly what you need to know if you scout them daily. Learn to read the bamboo stake or soil sampler and the mirliton leaves. They will tell if the vine needs water, and too much water can create a sick vine.

Use a Bamboo Stake or Steel Soil Sampler to gauge soil Moisture: Learn how to use a ½-inch bamboo tomato stake to test soil moisture in the root zone. It will tell you instantly if your vine has too much or too little available moisture. There’s a link at the end of this article to how to read the stake. Or buy a stainless steel soil sampler that allows you see and feel moisture levels beneath the surface (link below)

Check Guttation Daily: Mirlitons will tell you every day if they are quenched or thirsty. Guttation is the droplets of water that form on mirliton leaf edges early in the morning. The presence of guttation means the vine has more than enough available water in the root zone. Three days without guttation mean it probably needs watering. Check the vine first thing in the morning for guttation. Learn to read your mirliton leaves at the link below.

Wilting Does not Mean Water the Vine. A daily wilt in hot weather is normal and healthy mirliton. It’s called “leaf flagging” and it reduces exposure to direct sunlight and toughens the leaves against plant diseases. Watering mirlitons as a reaction to temporary wilt can actually harm the plant. When you see a daytime wilt, wait until the evening and probably see that it recovers.

Never give your vine a shower. That’s a surefire way to start an anthracnose epidemic. The anthracnose pathogens are primarily carried primarily by water through splash-up from the soil or splashed from leaf to leaf. Water gently at ground level with a hose on low, or use drip irrigation.

The Three Stages in the Mirlton Life Cycle:

1. Toddler:

Be careful with the baby. The first impulse when we see a young plant droop is to water our way out of the problem. Don’t do it At the toddler stage, mirlitons are most sensitive to soil moisture issues because their young roots are just emerging. Overwatering is the leading cause of premature death in mirlitons. Prepare for your toddler by installing gentle drip irrigation or an olla. Use the stake and read the leaves daily.

2. Sprawler:

Once the vine is established, it will begin to climb and sprawl. A larger canopy means they need more water. Daily summer showers should provide enough water, but don’t guess–use the stake and read the leaves.

3. Fruiter

The fall is fruiting season and water needs may increase, but use the stake and read the leaves.

Final Thoughts

Watering is not something you simply do to a mirliton vine; it’s something you do with it. It’s a partnership in which both parties have something to say. Listen to your vine.

Bamboo stake instructions here.

Steel Soil Sampler here.

Read the Mirliton Leaves here.

A Master Class in Mirlitons

Ervin Crawford And his Mirliton Vine

In 2008, I was searching for a Louisiana heirloom mirliton to replace the variety I had grown since 1983. The hurricane Katrina flood had killed almost every mirliton in New Orleans. The usual suspects had given me all the normal bad advice: “Buy one at the grocery store. A mirliton is a mirliton. They’ll grow fine.” Nope. I planted, they died; I planted, they died. Over and over.

After a little research, I discovered there were scores of varieties—perhaps hundreds—each adapted to the particular climate and altitude. I had to find the one traditionally grown in Louisiana. I discovered that the Louisiana Department of Agriculture’s monthly Market Bulletin was digitally archived years back. I went through it looking under “fruits and vegetables for sale” and saw one name repeatedly; Ervin Crawford, Pumpkin Center. It was a long shot because the advertisements were decades old, but I called the number. Ervin Crawford answered.

I immediately drove to Pumpkin Center and met him. On that first visit, Ervin gave me about 20 mirlitons and with those 20 plants, I started Mirliton.Org. Ervin played a crucial role in saving the Louisiana heirloom mirliton.

Visiting Ervin’s farm is a pilgrimage everyone should make. He’s a retired airline mechanic and knows more about mirlitons than anyone I know. He has been growing them for five decades, first in Peal River where he was raised, and later in Pumpkin Center where he bought his 20-acre retirement farm. He grows everything; pecans, figs, beans, berries, bees, chickens.

He has a quality found in most successful gardeners–a healthy curiosity. He wanted to know why he had success as well as failures. And failure and mirlitons often go together in the poor sandy pinewoods soil of the area called the Florida Parishes. I have heard people in the region say, “They won’t grow up here.” At first, I thought that they were using the wrong variety, or planting them incorrectly. Ervin taught that the problem was not the soil, it was what was beneath the soil.

Soil sample tests tell you a great deal, but they won’t tell you what you need to successfully grow mirlitons. Mirlitons are shallow-root plants and they sink or swim depending on subsurface drainage. If the soil doesn’t drain quickly enough, the roots can’t absorb oxygen, and the plant founders or dies. Building a raised bed on top of poorly-drained soil may result in a mud boat. The bed has to have an outlet to either absorb or remove excess water. So to succeed, you need to know the geology and history of the land you are gardening on–and Ervin asked the right questions when he first got to Pumpkin Center.

Ervin learned that Pumpkin Center’s soil was considerably different from Pearl River, where he had learned gardening. Pearl River was a loamy basin soil, rich and porous. In contrast, Pumpkin Center was in the middle of the great Piney Flats that stretches from Florida to Texas. It was notoriously bad poor soil—sandy and acidic. When he once had some excavation work done, he saw that solid white clay lay a few feet down–a real barrier to drainage.

I realized that I had never asked those questions about where I was gardening. To grow mirlitons, you have to be part geologist, hydrologist, and historian. You don’t have to become an expert; just enough knowledge to benefit your mirliton.

As I learned more about the history of where I was gardening, I realized that my mirlitons had often thrived in spite of me. I never once had asked what was under that topsoil or what was there 100 years ago.

I do now, thanks to Ervin.